Pop! Goes the Easel… An Introduction to Pop Art

November 23, 2015

After WWII, Atomic power and new technologies changed the entire dynamic of how art was perceived. Mass culture took over formality and breached subject matter conventions. This revolution is most commonly known as the Pop Art Movement. The term “pop” comes from the word “popular.” It is not a reference to Pop’s popularity, but to its focus on popular culture.

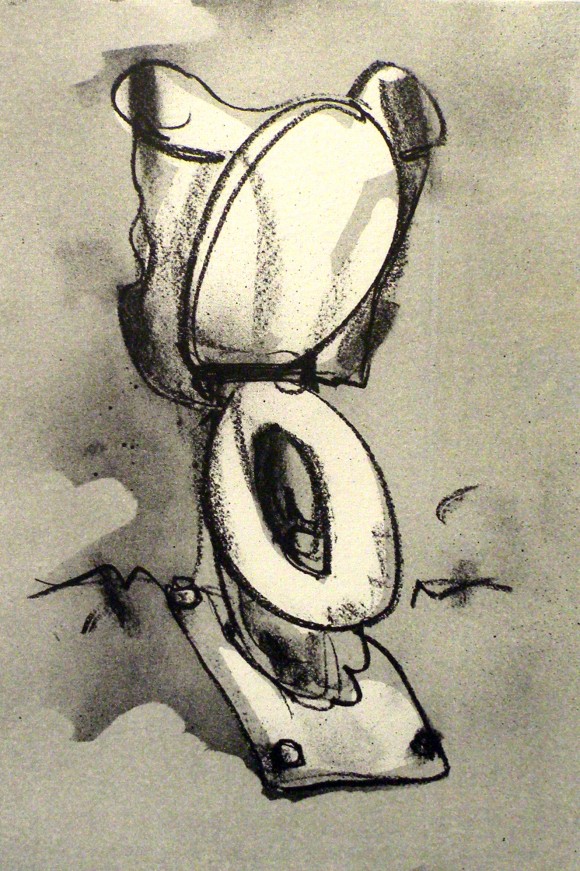

The commercialism that came after WWII influenced everyday life. Houses were filled with gadgets such as vacuum cleaners, iron boxes, refrigerators, and television sets. The world was becoming hip, and artists sought to capture the change that was taking place. Color was much brighter, and dimensions much flatter; there was a certain Pop! to art. Born around the mid-1950s, Pop Art is referred to as “the new realism.” It is mostly an American movement which employed techniques of commercial illustrations. Pop Art paintings are characterized as being cool and mechanical. Richard Hamilton, an English painter and collage artist, describes Pop Art as witty, expendable, glamorous, and young. Most pop paintings have a materialistic quality. Often, artists try to replicate newsprints, food labels, and advertisements by employing techniques of photographic screen printing and airbrush techniques to give their work a mass media shine. Some of Pop Art’s media sources include comic strips, advertising blow-ups, billboards, and television.

The experience of viewing Pop Art is similar to the feeling of rounding a sharp corner and being hit by a bicycle. If you have previously observed Roy Lichtenstein’s Mirror #5, my metaphor would make sense. Roy Lichtenstein, an artist in our collection, is very prominent in the Pop Art movement. The sharp, hard edges and bright colors are indications of that. More so, the borders of the painting are covered with tiny dots that are recognizable in most Lichtenstein paintings. These dots are called “Ben-Day dots” and are used in comic strips. By varying the size, color and spacing of the dots, a certain optical illusion is created. If you look closely at a newspaper, you can see the colored dots that are layered on top of each other, and Lichtenstein is stylizing that exact method. In many ways, his art is a symbol of commercial illustration.

Pop art has an ‘in your face attitude.’ Like Keith Haring’s Pop Shop V, for example. The painting has me squinting my eyes, and gives me no time to take it all in; it is very overwhelming, with an animated quality. In a blend of magenta, neon blue, and gaudy orange, the painting depicts what seems to be a man riding a whale. That ludicrousness is what is unique about Pop Art. And the gem factor of this art form is just that: a mix of crazy with a gigantic dash of intention. The message is very direct, and it does not attempt to make you guess what the author is trying to say. You do not have to go through a labyrinth of abstract thinking to deconstruct Pop Art. It is as linear and straightforward as it can be. Stark, bold, edgy, defined, sheer; Pop Art can be anything and everything, as Pop Shop V greatly exemplifies.

Born from commercialism, Pop Art is considered revolutionary. Not only does it breach the many boundaries of art, but it seeks to expand horizons. Andy Warhol, a very frank Pop Art artist, is the epitome of what Pop Art stands for. He turned everyday objects into works of art, such as his 200 Campbell’s Soup Cans. This painting is Pop Art, because of the familiarity of Campbell’s Soup cans. Painted in a mechanical manner, the soup cans resemble the shelves of a supermarket and portray the image of a commercial world.

To showcase a few more examples of Pop Art, here are a few hand-picked from our collection.

Recently, the LA Times published the article “5 pieces in the Broad collection that highlight Pop art history and its almost immediate impact” by Christopher Knight. The article features and deconstructs some of the Pop artists in our collection, and is a good reference to learn more about different Pop paintings.

All text and images under copyright. Please contact collections@chapman.ed for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.