Wind and Imagery of Migration: Interview with Escalette artist Bovey Lee

April 7, 2022

In celebration of Asian Pacific Islander Desi American Heritage Month, Escalette Director, Fiona Shen, joins Hong Kong-born artist Bovey Lee, to discuss the imagery of migration and the freedom of creative practice.

FS: So much of your imagery is airborne. I’ve noticed paper airplanes, balloons, streamers in the wind and birds, waves, sail boats, and animals and insects dependent on wind for migration. Can you talk more about this?

BL: It’s so interesting you pointed out all these airborne motifs, and they are a collection over many years, but when I look back at my work, I think they basically started after I moved to the US. What is interesting to me is how much I identify myself with this imagery. I mean, I love trees, mountains, things that are planted into the ground, but I relate myself, or my experience, with images that are in flight, that are suspended, that are floating, or constantly moving.

I think that is a space I am most comfortable with – that the space between lands is where I find myself most inspired. To me, that space represents adventure, a kind of unknown, whether it is through, for example, sail boats and airplanes (images that are directional, that have a destination, that imply in your mind you are setting out on a voyage or journey and you know where you want to head). Or whether it is more free-floating, like the balloons or paper boats, that on their own can’t go places because they don’t have a navigation system. They more or less just exist in the air wherever the wind blows them. So I find that these two states – a more conscious state of mind, and a more unconscious state – to be freeing. I think it has so much to do with the freedom I’m seeking in my own life. The only way to find that in my own experience is not to be completely set into the ground. I think this imagery speaks volumes to that when I look back. Because they’ve been so consistent, year after year. The airborne imagery is even a bit autobiographical; if you see yourself in your work, that’s where I see myself.

FS: You have a significant audience here in the United States, and I know that you’ve also had many commissions in Asia. How are these images received in Asia, especially in Hong Kong, where you were born?

BL: I feel that in Hong Kong people can relate to these airborne motifs because Hong Kong is such a small island and so densely populated. When people have time, the top thing on their list is to get out, travel. So that idea of travel has been implanted into our collective consciousness over a long time. And being an international port I think solidifies that mindset about the need to go out into the world and see the world. So I believe that the Hong Kong audience really knows where I am coming from, as far as why these images are so persistent in my work.

I think from the US perspective, I would imagine their interpretation would be closer to one of yours – because I’m an immigrant, it makes sense that of course I’m interested in this imagery that is suspended and in mid-flight, and moved by the bigger things, the invisible force of life, or even the elements, as you’ve said, like the wind or the water, because so much of our journey relies on this, right? We either have to take a boat or a plane to leave our native homeland, to build a new home in this new country. I think the perspective is different between the Hong Kong view and the US view. The sense of travel is not the same as seeking a new home in a foreign country.

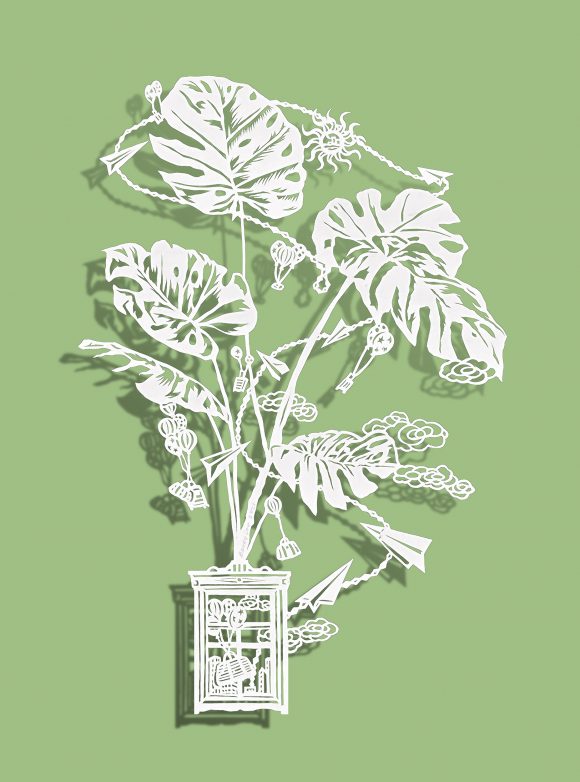

Bovey Lee, Patience–Lucky Bamboo (Outdoor), Cut Xuan paper on silk, 2021. 34.5×27.5 in. Image courtesy of the artist.

FS: You grew up in Hong Kong, and have chosen to work in the traditional Chinese art form of paper cutting. I can’t help but think of the Chinese concept of qi, or energy/breath, and wondered if you feel your wind-borne imagery evokes that?

BL: So with Chinese calligraphy, when we first started my teacher taught us how to control our breath, because the breath has so much to do with how the stroke is made on the paper. The ink is permanent, so there’s a lot of mind/body connection with the breath that we have to learn. When we finish the entire piece of calligraphy, we pin it up and look at it from far away, and what we’re looking for is not whether you wrote all the characters out correctly. What we’re looking at is to evaluate the qi of the whole piece – whether it shows a flow from character to character through the entire artwork. So the qi becomes a gold standard for good calligraphy. Somebody could be very good at writing the character with beautiful strokes, but if the whole integrity is not showing on the paper in the form of that flow, that qi, that energy, then it would just be technically proficient, but not good calligraphy.

What was planted in me and in my practice was to learn how to connect my breath when I’m creating my work. I’ve made this correlation many times. When I cut paper, why I am so drawn to it, even through it’s so laborious, is because it connects me to my body and my breath as a living being. I feel so alive when I’m creating cut paper, just like I feel so alive when I am focusing on creating a beautiful piece of calligraphy or art. So I think that sense of presence is so important, and the qi is what can bring you there. I think it manifests in the process of cut paper and certainly I hope it translates like a beautiful piece of calligraphy so that when people look at my work, I hope they see a sense of energy, movement and flow that is integral and integrated.

Header image caption: Bovey Lee, To Return (Hui), Cut Xuan paper on silk, 2021. 33x33in. Image courtesy of the artist.

—

We invite you to explore all the works in the Escalette Collection by visiting our eMuseum.

Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences is the proud home of the Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art. The Escalette Collection exists to inspire critical thinking, foster interdisciplinary discovery, and strengthen bonds with the community. Beyond its role in curating art in public spaces, the Escalette is a learning laboratory that offers diverse opportunities for student and engagement and research, and involvement with the wider community. The collection is free and open to the public to view.