April Bey, Atlantica, and Afrofuturism

February 9, 2021

“Afrofuturism” is a term you may have heard recently, perhaps in connection to the 2018 Black Panther movie or Octavia Butler’s science-fiction novels. It’s a word that has become more commonplace in pop culture and is provoking discussions about reimagined worlds and futures – but what exactly does it mean? April Bey, a Bahamian-American visual artist and art educator, is here to help. Bey incorporates Afrofuturism into her artistic practice as part of her interrogation of black culture, the African diaspora, post-colonialism, and social media.

April Bey, “You About to Lose Yo Job ‘Cause You Are Detaining Me, for Nothing,” Watercolor drawing on wood panel in archival epoxy resin. Hand-drilled holes and hand-sewn “African” wax fabric with oil paint impasto, 2020. Purchased with funds from the Ellingson Family.

The word “Afrofuturism” was coined by Mark Dery about 25 years ago in his essay “Black to the Future” (although musicians, artists, and writers were working within this tradition before it was given a name). In response to interviews with black creators working within the African diaspora, Dery asks if “a community whose past has been deliberately rubbed out, and whose energies have subsequently been consumed by the search for legible traces of its history, can imagine possible futures?” In defiance of the systems of repression that have shaped black history, Afrofuturists reimagine a future steeped in African traditions and black identity. More than simply a vision of the future, Afrofuturism is an unapologetic celebration of the innovations of Black cultures from around the world.

April Bey’s Afrofuturist work is centered around Atlantica, a fictional world where “power dynamics are destroyed” and where “people who may be seen as less than [on Earth] are more than [in Atlantica].” In Atlantica, those who would be oppressed on Earth are celebrated as deities and creators.

Welcome to Atlantica

On planet Atlantica, Grace Jones, Nina Simone and James Baldwin wear non-functional space helmets while smoking cigarettes in zero gravity because functional physics can’t impact their flyness. Their banners fly high in every governmental building where meetings are held only to discuss grits of glitter and shea butter application—glitter is our currency.

Atlantica [is] Bey’s home planet and also home to visionaries, Womanist Matriarchies, Earth analysis, black thought, and queer adventures in design. Atlantica is a joyous AfroFuturist meme and also a serious paean to women’s resilience in the face of colonialism, specifically black women who are expected to be sovereign and robust while at the same time assumed to be inept and emotionally weak when leadership roles are sought. Made in another universe that parallels, critiques, celebrates and satirizes our own, Atlantica occupies exploited space, offering up a fictitious world where labels are non-existent and we are allowed to float within our self-defined identities.

Source: https://www.nailedmagazine.com/features/artist-feature-april-bey

For Bey, focusing on the future is a way to expand narratives of Black history solely concerned with suffering to include Black success, innovation, and triumphs. In doing so, Bey wills the creation of a new aesthetic, and a new narrative, that exists beyond oppression.

“I have a hard time accessing art made that reflects Black pain and suffering now because all I can think about are the aesthetics of what the future could look like. If artists don’t start building that aesthetic now, how can we realize it in real life? Black death and suffering aren’t designed into my future, so I don’t want it illustrated in my present and especially so, my art. I’ve memorized it. I’ve mastered it. It’s redundant and overdone.”

Source: https://theundefeated.com/features/black-artist-series-redefining-blackness-april-bey/

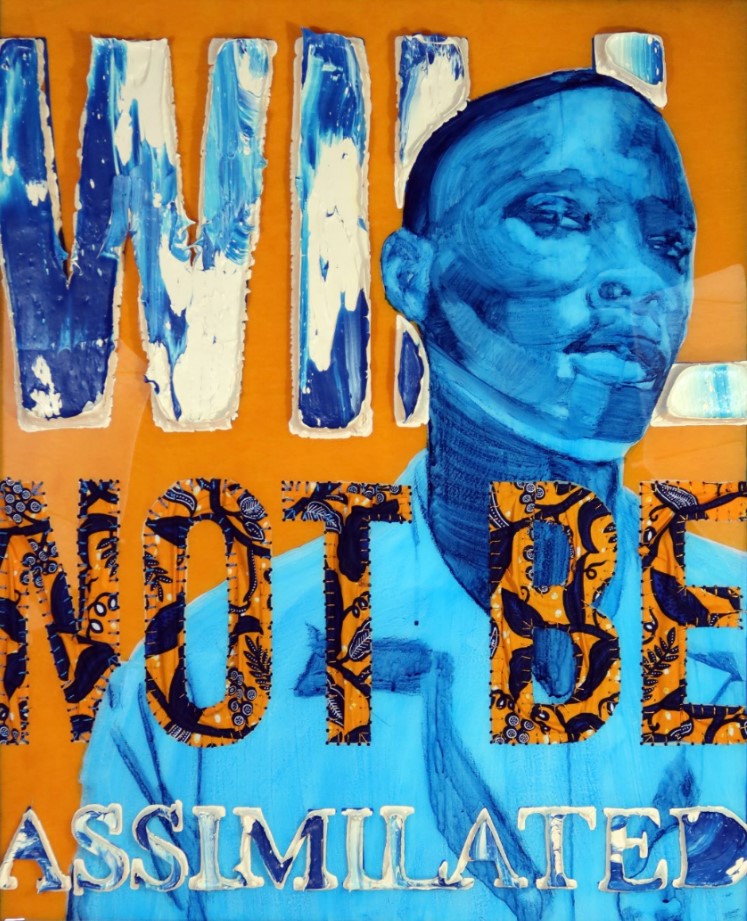

April Bey, They Say “I’m so jealous” but They Really Mean “Envious”, Watercolor drawing on wood panel in archival epoxy resin. Hand-drilled holes and hand-sewn “African” wax fabric with oil paint impasto, 2020. Purchased with funds from the Ellingson Family.

Even though Bey argues that her work removes “today’s climate entirely” in “imagining a futurist depiction of Black people freed from labels, colonialism and white supremacy,” her work (and any futurist work) inevitably reveals much about the present and the past.

Bey’s idea of Atlantica was inspired by her Black father, who used the idea of an alien planet to explain racism and colorism to her as a child. Bey describes how her father needed to explain “why I looked different than my mother, who was white, and why children at school made fun of my hair that stood up instead of laying down. He told me we would always be different because we were aliens sent from another planet to observe and report on Earth.” When she was older, Bey christened this nameless planet “Atlantica,” a world that is “is the therapeutic manifestation of April Bey — her origin story and a surreal coping mechanism to deal with existence as a queer Black femme on Earth.”

Like many of the other works in April bey’s Atlantica series, the two watercolor drawings in the Escalette Collection capture the neo-colonialism that takes place throughout the African diaspora. Bey was particularly struck by the Chinese knock-offs of traditional West African textiles she found during her travels to Benin, Togo, and Ghana. Bey hand-sewed this Chinese wax-fabric into the wood panels of the works (in the work above, the fabric makes up the words “NOT BE”) to comment on the globalization and corporate capitalism that continues to impact Black communities around the globe. That Bey uses this fabric to partly make up phrases such as “Will not be assimilated” or “I will not comply” suggests an ironic resistance to the forces of neo-colonialism that seek to erase Black tradition.

April Bey’s work shows that while Afrofuturism is concerned with the future, it is also deeply connected to the past and present. In reimagining a future free from oppression and racism, Bey and other Afrofuturists reveal much about themselves and the world they are living in now. At the core of Afrofuturism, is a celebration of Black culture and the hope for a more just future.

—

We invite you to explore all the works in the Escalette Collection by visiting our eMuseum.

Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences is the proud home of the Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art. The Escalette Collection exists to inspire critical thinking, foster interdisciplinary discovery, and strengthen bonds with the community. Beyond its role in curating art in public spaces, the Escalette is a learning laboratory that offers diverse opportunities for student and engagement and research, and involvement with the wider community. The collection is free and open to the public to view.