Adapting comedy for a new era: Farce and vaudeville in “A Flea in Her Ear” Student dramaturgs Dumas and Green offer insight into upcoming Dept. of Theatre production

February 11, 2016

Chapman University’s Department of Theatre chose to take on a French farce as its first production of the spring semester. A Flea In Her Ear, published by popular farceur Georges Feydeau (1862–1921) in 1907 and translated by acclaimed modern playwright David Ives (1950–) in 2006, has been a classic within both its genre and comedy itself for over a century. With history based in the Italian art of Commedia, farce contains comic elements of physical and satiric proportions that have delighted audiences through the ages. The truly outrageous circumstances within the piece are sure to shock and amuse even the most experienced theatregoer.

French playwright Georges Feydeau penned over 60 works, gaining fame at the height of the Belle Époque era. Though not a serious social critic, he capitalized on satirizing every new fashion while continuing to exploit all the more traditional forms of that age’s comedic characters – the female, the foreign, the old, the deformed, etc. His plots are improbable, usually dependent on farfetched cases of mistaken identity, and worked out in great detail without any consequent loss of speed. His comedic style took farce to new heights on the French stage. Farce began in France in the 15th century, where the term was first used to describe the combination of clowning, acrobatics, caricature, and indecency into one form of entertainment. Feydeau’s A Flea In Her Ear is considered a bedroom farce, which is heavy on indecency without ever giving too much away. Bedroom farces are centered on the sexual pairings and antics of characters as they move through improbable plots, and slamming doors. The comedy arises not from what we see on stage, but what we can only assume is taking place behind such doors.

David Ives, a contemporary American playwright, screenwriter, and novelist, was perfect to translate Flea because of his reputation for writing comic one-act plays. Theatrical farce survived into the early 20th century and found new expression in vaudevillian films with Charlie Chaplin and the Marx Brothers. Both farce and vaudeville use easily identifiable “stock” characters, trickery, and physical comedy. By infusing Feydeau’s farce with vaudevillian elements, Ives brings to light the nuances of the original script, and even, perhaps, reveals a bit more of what is behind those closed doors. Isn’t that what we all want to know more than anything?

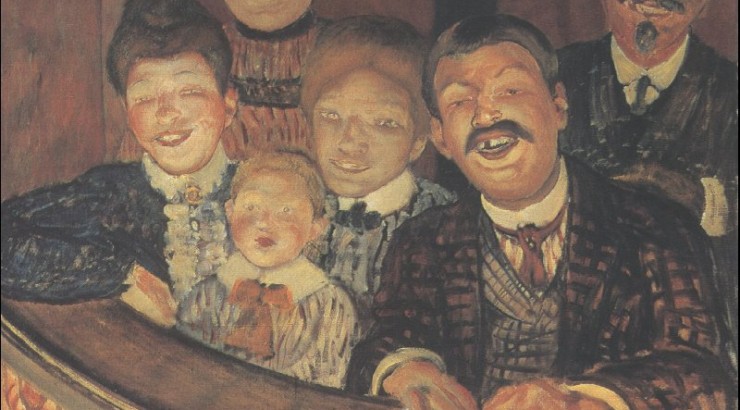

Image: “Theater Farce” by Petrov-Vodkin; Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=878199