“‘Americans, Americans,’ the angel said.”

September 28, 2015

“‘Americans, Americans,’ the angel said.”

The “angel” who spoke those words was a U.S. soldier, and the teenager who heard them in early May 1945 was a Lithuanian survivor of a death march from the Dachau concentration camp. His name was Solly Gaynor.

Solly’s angel didn’t look at all like he had imagined. Puzzled at first, Solly thought his liberator must be a Japanese soldier, but instead of speaking Japanese, the soldier spoke English and wore the uniform of the U.S. Army. He said to Solly: “‘You are free, boy. You’re free now.” Then he reached into his pocket and handed Solly a piece of chocolate. The soldier’s name was Clarence Matsumora (

Light One Candle: A Survivor’s Tale from Lithuania to Jerusalem

, p. 347).

What Clarence did not tell Solly in their brief encounter was that he was a member of the 442nd Regimental Combat Unit, a unit composed entirely of Nisei, second generation Japanese Americans. Like many other young men, Clarence had enlisted to fight for his country.

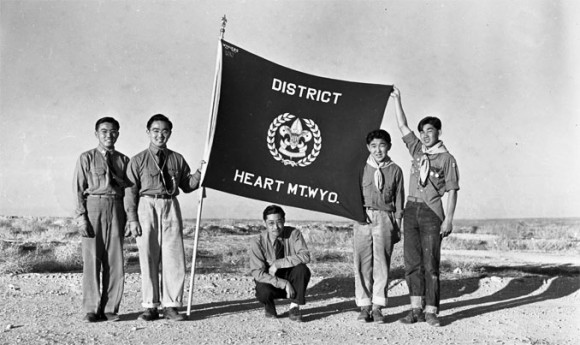

Many of those fighting alongside Clarence had family members in so-called “relocation camps.” Before Pearl Harbor, they had been living in California, Washington State, or Oregon, but as a result of Executive Order 9022, signed by President Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, they had been ordered and sent, with little notice, from their homes to camps in the interior U.S. Surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers, the hastily prepared sites were located in inhospitable places like Heart Mountain in northwest Wyoming.

On

Thursday, October 1, at 7 p.m. in Memorial Auditorium

the Rodgers Center will co-sponsor a

screening of the documentary

Witness: The Legacy of Heart Mountain

followed by a panel discussion. The event is sponsored by the Department of Sociology in Wilkinson College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Sciences and is the result of the dedication and hard work of my colleague, Dr. Stephanie Takaragawa.

Even now, seventy years later, it is hard to believe that fear, racism, and economic jealousy could so quickly lead people to view their neighbors, friends, and in many cases, their fellow citizens, as potential traitors. Yet, that is exactly what happened here in Southern California. Many were sent to Heart Mountain.

Uncertain when, if ever, they could return home, they sought to replicate as best they could their former lives. Kevin Starr, the historian of California and former State Librarian, writes:

The Boy Scout troops seem so American, as do the bobby soxer attire of the teenagers. . . . Christian internees attended church on Sunday, just as they would in their home towns. All these people and things seem so American because they were American. [italics mine]

And certainly, above all else, the Japanese-American men and women who served in the Army and the Women’s Army Corps seem so very American. . . . Altogether, the two largest Japanese-American units, the 100th Infantry Battalion and the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, suffered 9,486 casualties. . . including 650 killed in action. . . . If they had been one unit, it would be the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in the entire history of the United States (Embattled Dreams: California in War and Peace, 1940-1950, pp. 94-95).

The men in Clarence’s unit not only served their country, they served with exemplary valor. For my colleague Dr. Takaragawa, their story and the story of the Heart Mountain camp are deeply personal. It is not only history; it is family history. Her father was born in Heart Mountain and both her maternal and paternal grandparents lived there.

Solly Gaynor kept the chocolate that Clarence gave him that day. As he wrote in his memoir: ”You just don’t eat treasures.” (p. 347) But the real treasure that day was not chocolate. The real treasure was freedom, and it was represented by an American soldier who just happened to be of Japanese ancestry.

It is a story to remember and ponder.

The event begins on Thursday, October 1, at 7 p.m. in Memorial Hall on the Chapman University campus. There is no admission fee.