Szneer and Lubenewski Families’ Papers Piecing Together Fragments in the Archive

November 3, 2023

“…there is something utterly mysterious in old photographs, that they are almost designed to be lost, they’re in an album which vanishes in an attic or in a box, and if they come to light they do accidentally, you stumble upon them. The way in which these stray pictures cross your paths, it has something at once totally coincidental and fateful about it. Then of course you begin to puzzle over them, and it’s from that that much of the desire to write about them comes.” [1] – W.G. Sebald

Isabelle (left) and Leopold Szneer (right) in Blankenberge, Belgium, 1949 [2]

On November 7, 2023, the Rodgers Center for Holocaust Education will commemorate Kristallnacht, the series of pogroms against the Jews of Germany and Austria by the Nazis that took place November 9 – 10, 1938. The Oskar Schindler Archive holds materials from Jewish Holocaust survivors who witnessed the Night of Broken Glass. Among them is Cantor Leopold Szneer who was born on December 21, 1921, in Munich, Germany. From an early age, he studied Chazanut (cantorial singing) and performed as a soloist in his synagogue’s choir. Post-World War II, he emigrated to the United States with his wife, Isabelle, and settled in Los Angeles where he served as Cantor at the Congregation Mogen David in Los Angeles, California for more than 20 years.

Leopold Szneer singing, circa 1946-1960 [3]

Kristallnacht

Leopold was arrested during Kristallnacht and sent to Dachau concentration camp. On the 75th anniversary of Kristallnacht at Chapman University, he recounted his experience:

“I wanted absolutely to see my synagogue. My parents, may they rest in peace, never agreed to this. A day goes by, another day, it is November the 12th. And I did like some other kids do today, not listen to my parents and I swindled myself out. I went to the synagogue… it was a catastrophe. And people were around there and were speaking to each other…so I said to the people, “isn’t it a shame what they did to this synagogue?” But it didn’t take long, I was taken from both sides. Two men… take me away. Where did they take me? To Dachau. I was sixteen years old.” [4]

Fragments and Traces

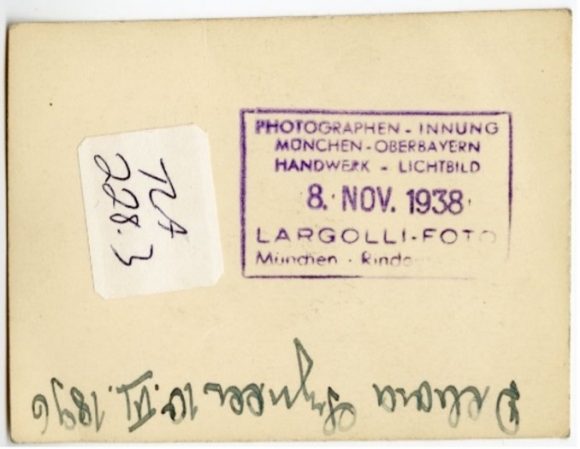

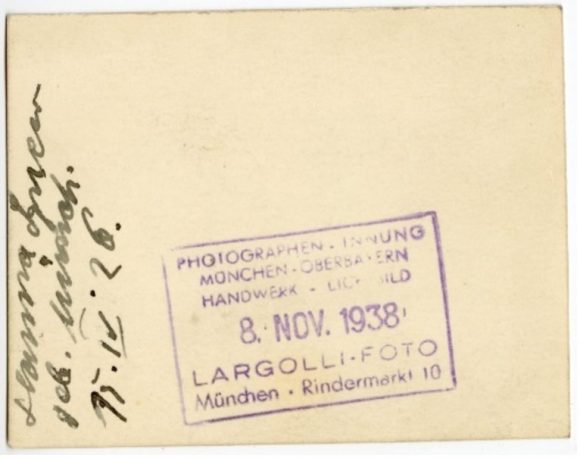

During this past summer, while completing a reference request, I stumbled across stamps on the back of three photographs. They were portraits of Leopold, and his mother, Dwojre (Dora) Szneer and youngest sister, Hanna Szneer. The stamps piqued my curiosity because they retained the dates: November 8, 1938, one day before Kristallnacht, and November 15, 1938.

(Click images to see full size)

Portrait of Leopold Szneer, 1938 [5]

Portrait of Dwojre (Dora) Szneer, 1938 [6]

Portrait of Hanna Szneer, 1938 [7]

It is likely these photographs were intended for passports which would document the Szneers’ attempt to leave Munich, Germany shortly before Kristallnacht. But by the time Leopold’s photograph was developed on November 15, 1938, he had already been arrested only three days prior and imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp.

While observing the photographs, you will notice the information on the back of Leopold’s differs from the rest. Hanna and Dora’s photographs were developed on November 8, 1938 (one day before Kristallnacht); however, Leopold’s photograph was not developed until November 15, 1938. Leopold’s photograph also contains “Israel” before his name, following anti-Jewish legislation in pre-war Nazi Germany. The law required all German Jews bearing first names of “non-Jewish” origin to adopt an additional name: “Israel” for men and “Sara” for women.

You will also notice the stamps are faded in different spots, but a complete picture can be discerned when viewing all three photographs together. The spot where one stamp is faded, the ink on the other two stamps is bold enough to fill in the missing information, thus making the stamp legible. The photographic studio stamp belongs to: Largolli-Foto, München, Rindermarkt 10 [Largolli-Photo, Munich, Rindermarkt 10]. Through further research, I discovered photographs with the same Largolli-Foto stamp on the University of Oregon’s Mir Website and in Constanze Werner’s Kiew-München-Kiew: Schicksale ukrainischer Zwangsarbeiter.[8]

Archival Value

The Szneer photographs are important historical resources for both research and visual commemoration. As an archivist, identifying information on the back of the photographs helps me create descriptive metadata to improve discoverability for researchers. But they are also fragments of a life and history waiting to be discovered further.

A former 2019-2023 Presidential Fellow at Chapman University, Glenn Kurtz writes about piecing together such fragments from multiple archival materials in his book, Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film. Over the course of 4 years, he attempted to identify the people in his grandfather’s three-minute film of the Jewish community in the Polish village of Nasielsk in 1938. Kurtz writes:

“Fragments of memory intersected with fragments of film, with fragments found in the few documents that exist, in postcards, letters, photographs, and artifacts. And in the interconnections of these surviving fragments, I began to catch fleeting glimpses of the living town…Like my grandfather’s film, the fragmentary history I assembled preserves a little of the town’s vibrant complexity, the details that made its life and death distinct from others and made these people different from millions like them.”[9]

Are you interested in discovering more about this collection? Dig into the Szneer and Lubenewski families papers in the Oskar Schindler Archive reading room.

Notes

[1] James Wood, “An Interview with W.G. Sebald,” Brick, A Literary Journal, no. 59 (Spring 1998): https://brickmag.com/an-interview-with-w-g-sebald/.

[2] Isabelle and Leopold couple, bulk: 1946 – 1949, document-box: 2, Folder: 5. Szneer and Lubenewski families papers, (2020-006-h-r.), Oskar Schindler Archive, Chapman University, CA. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/5780 Accessed October 25, 2023.

[3] Leopold Szneer, bulk: 1946 – 1960, document-box: 2, Folder: 2. Szneer and Lubenewski families papers, (2020-006-h-r), Oskar Schindler Archive, Chapman University, CA. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/5777 Accessed October 25, 2023.

[4] Chapman University, “Holocaust Survivor Cantor Leopold Szneer’s Perspective on Kristallnacht,” Youtube Video, 8:06, September 22, 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0uWFN5rpjw.

[5] Leopold Szneer, bulk: 1922 – 1938, document-box: 2, Folder: 1. Cantor Leopold and Isabelle Szneer collection, (2020-006-h-r.), Oskar Schindler Archive, Chapman University, CA. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/5776 Accessed October 18, 2023.

[6] Moses and Dora Szneer, bulk: 1930 – 1938, document-box: 2, Folder: 12. Cantor Leopold and Isabelle Szneer collection, (2020-006-h-r.), Oskar Schindler Archive, Chapman University, CA. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/5788 Accessed October 18, 2023.

[7] Szneer family portraits, bulk: 1922 – 1934, document-box: 2, Folder: 10. Cantor Leopold and Isabelle Szneer collection, (2020-006-h-r.), Oskar Schindler Archive, Chapman University, CA. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/5/archival_objects/5786 Accessed October 18, 2023.

[8] Constanze Werner and Verein Projekt Erinnerung e.V. 2000. Kiew-München-Kiew : Schicksale Ukrainischer Zwangsarbeiter. (München: Buchendorfer, 2000), 46, 93,129.

[9] Glenn Kurtz, Three Minutes in Poland: Discovering a Lost World in a 1938 Family Film, First paperback ed. (New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2015), 8.