Becoming History’s Stagehand Abigail Stephens, '26

October 24, 2024

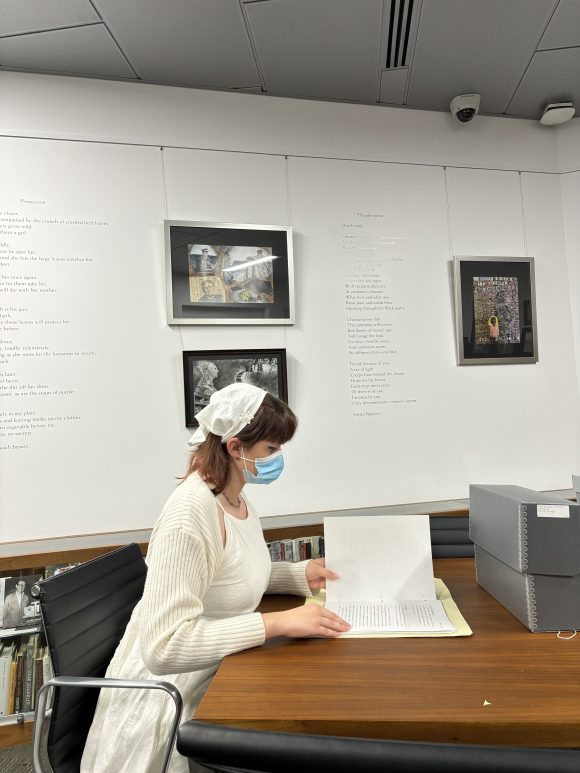

Abigail Stephens, ’26 is a History major and is minoring in Journalism and CCI (Creative Cultural Industries). She is also the student library assistant for the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library and Oskar Schindler Archives.

In December 2023, I finished my first semester as the student library assistant for the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library and Oskar Schindler Archive. While I have always been captivated by careers centered on history, adults have repeatedly warned me that the spark might fade when I get my first real archival job. “It’s not glamorous”, they warned. “It’s quiet and tedious and further in the background than more spotlighted subsections of academia, such as professors or authors.”

In December 2023, I finished my first semester as the student library assistant for the Sala and Aron Samueli Holocaust Memorial Library and Oskar Schindler Archive. While I have always been captivated by careers centered on history, adults have repeatedly warned me that the spark might fade when I get my first real archival job. “It’s not glamorous”, they warned. “It’s quiet and tedious and further in the background than more spotlighted subsections of academia, such as professors or authors.”

After a few months, I came to the conclusion that my mentors were mostly correct. Archives are quiet, out of the spotlight, and demand astute attention to sometimes tedious tasks – and yet my spark for them has failed to fade. Working behind the scenes, I have fallen in love with being history’s stagehand, piecing together the past and presenting it to a curious audience—and even to people whose curiosity hasn’t been evoked until now. I wish for each audience to become a witness, firmly aware of the events of the Holocaust despite our ever-growing distance from the past.

As a library assistant, I help organize and maintain physical and online research material. These materials may include books, newspapers, photographs, government documents, personal papers, diaries, and letters — objects revealing details, often minute, about a specific subject or event. Through this work, I can provide accurate, historical information to a variety of researchers, from academics writing essays to families hoping to learn more about a relative’s lived experiences.

A common misconception about the Oskar Schindler Archive is that it houses only collections pertaining to its namesake, Holocaust rescuer, and Righteous Among the Nations, Oskar Schindler. While a large portion of our collection is source material about Oskar and Emilie Schindler, I most often work with collections donated by local Holocaust survivors and their families.

My favorite task is filling in the blanks of these collections, such as finding dates for documents or translations for testimonies. Scavenging for information through the smallest details can feel like detective work. Some of my most memorable cases come from determining birth and death dates missing from our collection. What might seem like a simple job has me foraging through one hundred-year-old censuses, obituaries, and birth certificates, tracing family trees back generations.

Surprisingly, translating documents yields a similar process. A simple Google translation from German is often not sufficient. Instead, I pour over handwriting comparisons, cursive guides from the 1940s, and international archives to parse through a piece of text.

While working through boxes of material painstakingly put together by survivors, I discovered that archival work is an unsung way of bringing people justice. These individuals experienced trauma unimaginable to a woman in my position, and yet survivors – and their families – tirelessly documented materials about those experiences to donate to the archive. In fact, most, if not all, of our non-Schindler-related items come from individuals directly impacted by the Holocaust. It is through relentlessly recording their experiences that aging survivors pass on memories. They hope that, if preserved, history will act as a conscience, preventing people from repeating past mistakes. It is my job as an archivist to protect their memories and make them available for the next generations in the hope that by so doing, I can offer our visitors the tools to make their own meaning and derive their own lessons from the Holocaust.