Setting our Students up for Long-Term Success Six Steps to Crafting Opportunities for Fulfilling and Sustainable Employment

January 8, 2021

By: Rachel Wiegand, Amy Jane Griffiths

Introduction

Imagine a former student with a disability arriving at her newly earned place of employment. As a member of her Transition-Focused IEP Team, you, your student, and all stakeholders collaborated extensively to ensure that her transition plan met her needs, suited her interests, and aligned to her long term goals. These efforts are reaffirmed as her first day unfolds–she arrives at a workplace she is familiar with, for a position she wanted and is prepared to fulfill.

But what happens if the career path that we encourage her to pursue is not sustainable? What happens if six months, two years, or six years down the line, the job that she tirelessly trained and prepared for no longer exists?

As the working world around us continues to evolve, so do the ways we prepare our students for the future. According to some estimates, 85% of the jobs students will be hired for in the year 2030 have yet to be invented (Institute for the Future & Dell Technologies, 2017). Despite these realities, there is currently limited research on how we ensure our students with disabilities have sustainable career paths in our rapidly evolving workforce.

While our field has made strides in readying students for post-secondary life, employment rates continue to highlight the need to prioritize transition planning that will lead to more successful post-graduation employment (BLS, 2018a). In the United States, 68% of individuals without disabilities participate in the workforce versus 21% of individuals with disabilities (BLS, 2018a). Regardless of age, a person with a disability is less likely to secure employment than a typical peer. Overall, the outlook for persons with disabilities related to employment continues to trail significantly behind those without disabilities (Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS], 2018a).

In this study, the authors consider how to integrate labor market data into Transition-Focused Individualized Education Programs (TF-IEP) by providing a brief analysis of the most in-demand skills and jobs in Orange County, California, and the United States, and six steps on how to integrate this data into the planning process.

High-Demand Skills & In-Demand Jobs

To better understand the relationship between supply and demand of various skills, we compared how often employers listed skills in job postings to skills that are prominent in today’s labor force. This resulted in a dataset consisting of over 100 million resumes and profiles, with job posting information. The skills represented in this set of applicant profiles include individuals with a diverse range of experience and education (Walrod & Walrod, 2018).

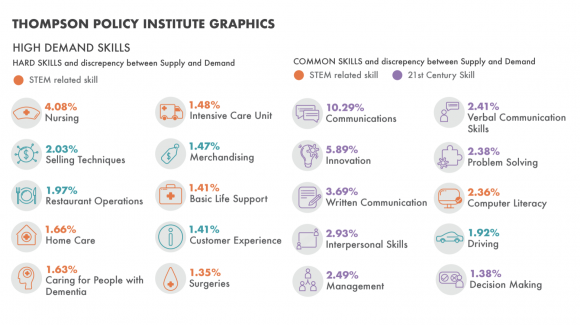

Skills were categorized as either “hard” skills, which are more tailored to specific jobs, and “common” skills, which are broader skills that are not typically job-specific. The top 10 in-demand hard and common skills are listed in Figure 1. Beside each skill, the percentage indicates the discrepancy between supply (number of prospective applicants who list this skill) and demand (number of employer listings soliciting the skill). In each skill area, demand exceeds supply. The higher the number, the greater the discrepancy.

With these skills in mind, individuals with disabilities, and the educators who work alongside them, may begin to create a more robust TF-IEP that is geared toward more long-term career sustainability

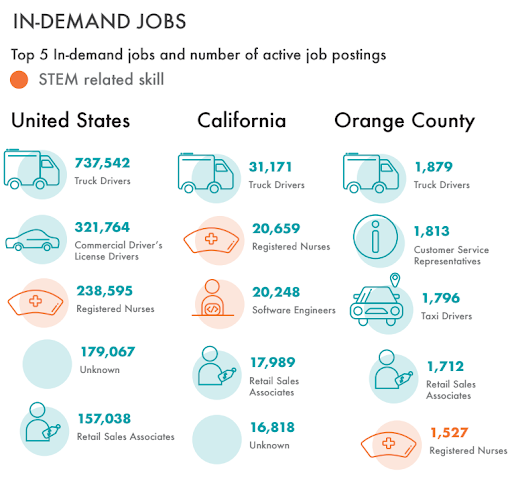

To effectively assist students in planning for resilient and sustainable futures, it is also helpful to have information on in-demand jobs. Figure 2 reflects the top five most available jobs in the United States in the last two years.

Figure 2. In-Demand Jobs

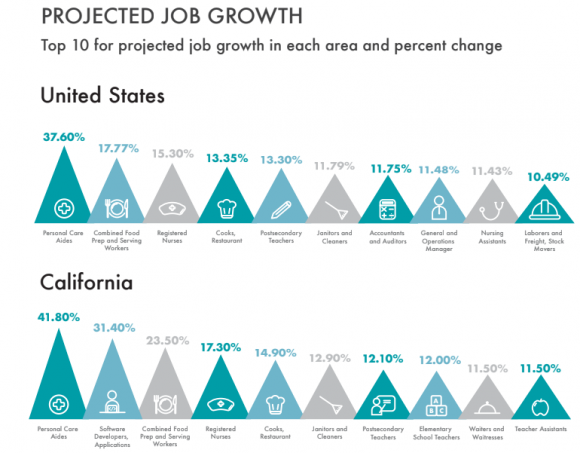

Figure 3 shows projected job growth, calculated by evaluating the percentage change in the most common careers across the next ten years in the most common careers. This chart includes data for the United States, California, and Orange County to illustrate similarities and differences by region. Once a clear picture of current and future labor market needs is established, educational professionals can use this information to follow a six-step transition planning process in developing TF-IEPs that better emphasize long-term career sustainability.

Figure 3. Projected Job Growth

Six Steps to Crafting Transition-Focused IEPs

Step 1 – Strategies for assessment of strengths and needs

The first step in crafting a TF-IEP is to assess the student’s strengths and needs while also considering the area’s current labor market needs. This step includes identifying and evaluating both hard skills and common skills based on the learner’s potential career interests. Questions to consider throughout this step include:

- Do the assessment outcomes (e.g., suggested occupations) match up with the current and future projected labor market needs (figure 1 and 3)

- If there is a discrepancy between the assessment data and current labor market needs, what data do we need to begin the planning process?

- What skills will our students need to be successful, and what can we do as teachers to assist them?

Step 2 – Developing a vision and goals

Inviting students to develop a plan and a vision for their future is critical in ensuring future success. The TF-IEP team can rely on assessment data to pinpoint students’ strengths and individualized needs, and the climate of the job market in their local area.

Considering the question below will ensure that teams are incorporating the realities of their current local labor market into the planning process, and as result, developing relevant and impactful goals for their students.

- How (if at all) has labor market data been used in the Step 1 assessment process to guide planning?

- How connected is the plan to current and future labor market needs? (figure 3)

- Does the plan lead to sustainable employment or outcomes for the student?

- Does the plan include hands-on opportunities for the student to practice and receive feedback on necessary skills?

- Does the TF-IEP match student strengths, goals, and needs with the identified labor market gaps? (figure 3)

- Does the data collection plan incorporate information that would prepare students for long-term employment?

Step 3 – Building a strong team

In order to assist students in working towards an “enviable [post-secondary] life” (Turnbull, 2010) that leads to sustainable employment, schools must assemble a strong team. All team members have an essential role in assisting the individual as they progress towards their goals. Students must take an active role in deciding what their future will look like and benefit from teacher-guidance and routine application of self-determination skills (Shogren & Ward, 2018). Team members often include relevant community members (e.g., employers, college representatives, vocational rehabilitation counselors, medical providers, etc.). Vocational rehabilitation counselors can assist in labor market analyses as it is a required component of their role in constructing the individualized plan for employment (IPE). Collaborating with parents is also a critical part of the planning process. Engagement should begin with the onset of the school year. Establishing culturally responsive practices is critical and can lead to more effective partnerships when working with families from diverse backgrounds (Povenmire-Kirk, Bethume, Alverson, & Kahn, 2015).

Step 4 – tools for skill-building

As members of TF-IEP team, stakeholders should assist in identifying evidence-based approaches for teaching skills students will need in the dynamic, modern workplace. By aligning instructional tasks to a student’s chosen career-path, teachers can create opportunities that develop academic skills and progress students towards their transitional goals (Bartholomew, Papay, McConnell & Cease-Cook, 2015). Building relationships within the community also allows educators to secure potential work-based learning opportunities for youth (Bellman, Burgstahler & Ladner, 2014).

Step 5 – practicing skills

As students acquire various skills, educators can provide them with frequent and systematic opportunities to practice them. This might include participating in internships or volunteer positions where students can develop skills in relevant environments. Instructors should plan for ways to support learners who experience setbacks or challenges throughout this process. To foster occupational awareness (Papay et al., 2015) and assist with generalization of skills, teams should consider programming that includes career exploration, exposure to mentors, and community-based learning (Bellman, Burgstahler & Ladner, 2014).

Step 6 – progress monitoring and reevaluation of goals

After youth received feedback from those around them on newly attempted skills, the team can determine a course of action based on their progress.

This 6-step process is intended to be employed continuously. The team will regularly monitor progress towards goals, revisit labor market trends to align local employers’ needs with students’ skills, and select evidence-based supports and relevant programming. Effective teams should regularly collect information on the ever-evolving job market and consistently engage in the process of crafting and adapting plans in response to trends in the labor market and student data.

Conclusion

By using detailed labor market data throughout the drafting of TF-IEPs, students can access more sustainable careers, hopefully resulting in an increase in long-term employment rates for individuals with disabilities. Labor market data analysis includes identifying projected job growth, in-demand jobs, and high demand skills. Once a school team gathers this information, they can align these trends to their students’ strengths and interests as potential hires. By considering our local and national labor market’s current and future state, we can create TF-IEPs that will lead to sustaining, successful employment of our learners with disabilities after graduation and for many years to come.

References

Bartholomew, A., Papay, C., McConnell, A., & Cease-Cook, J. (2015). Embedding secondary transition in the common core state standards. Teaching Exceptional Children, 329-335.

Bellman, S., Burgstahler, S. & Ladner, R. (2014). Work-based learning experiences help

students with disabilities transition to careers: A case study of University of Washington Projects. Work, (48), 399-405. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-131780

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, Persons with a Disability: Labor Force Characteristics News Release. (2018a). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/disabl.htm

Institute for the Future, Dell Technologies. (2017). The Next Era of Human Machine

Papay, C., Unger, D. D., Williams-Diehm, K., & Mitchell, V. (2015). Begin with the end in mind: infusing transition planning and instruction into elementary classrooms. Teaching Exceptional Children, 310-318.

Povenmire-Kirk, T. C., Bethume, K. L., Alverson, C. Y., & Kahn, L. G. (2015). A journey, not a destination developing cultural competence in secondary transition. Teaching Exceptional Children, 319-328.

Shogren, K. A. & Ward, M. J. (2018) Promoting and enhancing self-determination to improve the post-school outcomes of people with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 48(2), 187-196.

Turnbull, A. (2010). Transitioning to enviable lives for adults with Autism; and Beyond evidence-based practice: Wisdom-based action as a process of facilitating IDEA outcomes. Mollie Villeret Davis Lecture. Retrieved from https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/74308

Walrod, W., & Walrod, P. (2018). Labor market analytics report [Internal unpublished report]. Available at https://www.qidianusa.com/