Meet the Faculty: Dr. Bart Wilson Donald P. Kennedy Endowed Chair in Economics and Law

August 29, 2019

Dr. Wilson is the Donald P. Kennedy Endowed Chair in Economics and Law at Chapman University. He is a member of the Economic Science Institute and Director of the Smith Institute for Political Economy and Philosophy. His research uses experimental economics to explore the foundations of exchange and specialization and the origins of property. Another of his research programs compares decision making in humans, apes, and monkeys.

Dr. Wilson has published papers in the American Economic Review, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. His research has been supported with grants from the National Science Foundation, the Federal Trade Commission and the International Foundation for Research in Experimental Economics. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Arizona.

What research or publication are you most proud of completing and why?

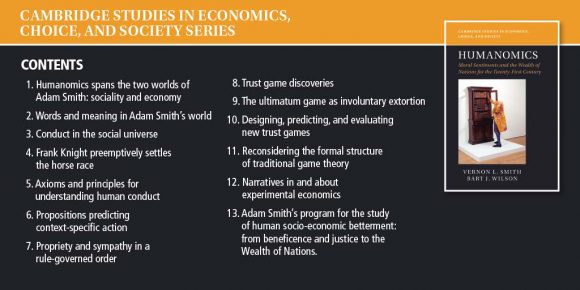

In January 2019, Vernon Smith and I co-authored a Cambridge University Press book entitled, “Humanomics: Moral Sentiments and the Wealth of Nations for the Twenty-First Century”. The book is a product of ten years of reading Adam Smith, the founder of economics, with students and many more years of unlearning everything I learned in graduate school in order to understand Adam Smith on his own terms. I am proud of the publication because it came out of the classroom and our desire to read Adam Smith with students. I’m also proud because it informs what we are doing right now in experimental economics.

What is the most important lesson you hope your students walk away from your classroom with?

I hope that students leave my classes with the ability to think critically, to be able to take ideas from primary texts and give them new forms. I teach Humanomics courses where students read economics concurrently with philosophy and literature. I would like my students to make connections between different texts and say something original about them. I want my students to be able to think on their own and be novel about it.

Do you have any examples of Humanomics in the classroom?

During Interterm Prof. Katharine Gillespie Moses and I co-taught Milton’s Paradise Lost, an epic poem about The Fall in the Garden of Eden, with Thomas Sowell’s book entitled, Knowledge and Decisions. Questions in economics are often posed in the form of “What should be done?” Thomas Sowell frames his book around the question of “Who shall decide?”, which is a major theme of Paradise Lost. Adam and Eve were free to choose to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. The human constitution is, as Milton says of Adam and Eve, “sufficient to [stand], though free to fall.” In economics, as in anything, we can decide, and we can decide badly. We have the liberty to decide, but that also means, like with Adam and Eve, that we must take responsibility for what we do.

What makes your class different and why should students take the class?

My class is different in that it is organized around reading, discussion, and writing. It is a class where students can develop their writing and communication skills. During the Interterm course, the students wrote every day, around 250 polished words, with the goal of saying something original. It is a class where students can focus on economics while also practicing their thinking and writing.

What is the accomplishment you are most proud of in your career? What goal are you working towards?

I am currently finishing my next book entitled, The Property Species, which is slated to be released by Oxford University Press in July, 2020. This is my first solo book, which I am very excited about. I argue from some hard-to-dispute facts that neither the natural sciences, nor the humanities, nor the social sciences are synthesizing a full account of property. I make the claim – sure to be controversial – that property is a universal and uniquely human custom. I argue that all human beings and only human beings have property in things, and at its core, property rests on custom, not rights. You may think your dog has property in his toys and territory, but I aim to convince you that “I want this” is not the same thing as “This is mine,” and that it is a marvel of natural history that only humans say about things, “This is mine,” and respectfully, “That is yours.”