Regionalism Its role in defining "American Art"

July 25, 2016

Regionalism was an American art movement that emerged in the Midwest in the early 1930s and continued into the early 1940s. While Grant Wood, the leading artist of Regionalism and creator of the infamous American Gothic painting, considered the movement to be a new type of modern art, Regionalism also has deep historical roots in American art such as the the romantic landscape painting of the Hudson River School (1860s). At the height of the movement in the 1930s, Regionalist artists drew most of their subject matter and inspiration from local traditions such as the Midwestern farm landscape and the history of the native Midwest region. Regionalism’s propensity towards traditional American values and lifestyles became especially popular during the Great Depression as a symbol of the strength and endurance of the American people. During the Great Depression in the 1930s, Regionalism became the unofficial style of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the Federal Art Project, and the Treasury Section of Painting and Sculpture, all of which provided employment for artists through mural and painting commissions.

Regionalism is often considered a reactionary movement that rejected the avant-garde art of Picasso, Matisse, Duchamp, and other European painters in favor of a more representational, realist style of art. The rejection of these European modernist artists was largely symptomatic of the prevailing desire to create a new indigenous, modern, American art that was free of foreign influences. Abstract Expressionism, which was founded in New York, similarly sought to create a new American art, but employed a much more liberal, abstract stylistic approach. Regionalism became entrenched in a debate over what kind of art was to become the new American modern art. The Regionalists, whose work was realist, centered on rural life, and promoted by conservative critics, was positioned at one end of the spectrum while abstract artists, who primarily lived in New York and were promoted by more Pro-Modernist, liberal critics, was positioned at the opposite end. As the Abstract Expressionists emerged, Pro-Modernist critics used their influence in the art world to advocate abstract art over Regionalism. As a result, Regionalism has become a more neglected and often misrepresented area of art history. The success and widespread acknowledgement of the Abstract Expressionists at the expense of the Regionalists was facilitated by differences in social class and economics; the patrons and critics of abstract art were among the wealthiest class of people in America at the time, while the patrons and supporters of Regionalist art included considerably less wealthy and influential Federal WPA programs and middle-class locals. The location of the Abstract Expressionists in New York also provided a greater national and international platform for promotion than did the small towns in the Midwest where the Regionalists lived and painted.

In some ways, however, Regionalism and Abstract Expressionism exhibited a less dichotomous relationship than previously thought. Just as the Post-Impressionists (Cézanne, Van Gogh, Renoir, Gauguin, and others) connected representational and abstract art in Europe, Regionalism served to bridge the gap between strictly realist academic art and completely abstract art. Regionalism served as a transitional style that is significant in its own right, but was also influential in that it helped to pave the way for Abstract Expressionism and contributed to the ever-changing definition of “American art.”

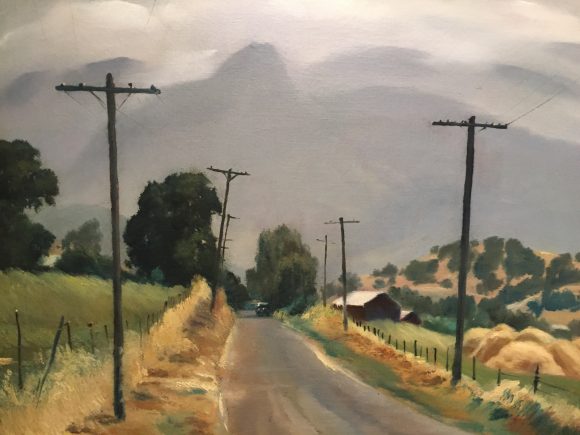

Several paintings in the Narrative Visions exhibition at the Hilbert Museum were part of the Regionalist movement and reflect the movement’s history. Esso by Barse Miller, for example, captures the Regionalist fascination with the small, rural towns of the Midwest. During the 1930s and 1940s, Miller became an established painter whose most celebrated works include those that capture the everyday life of small-town people during the Great Depression. Many of his paintings were based on the scenes he encountered while traveling throughout California. Emil Kosa Jr. likewise painted scenes that represent the endurance of rural people during the Great Depression. Kosa Jr. painted Driving Along the Old Road while working on the legendary 20th Century Fox Studios film,The Grapes of Wrath in the special effects department. The scene reflects both the storyline of the film and the rugged beauty of the Midwest landscape that captured the attention of Regionalist artists.

Come by the Hilbert Museum and take a tour of the abstract works in the Escalette Collection on campus to see how Regionalism and Abstract Expressionism sought to define “American art.”

All text and images under copyright. Please contact collections@chapman.edu for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.