Identity Stolen and Regained Reflections on The Woman in Gold

September 3, 2015

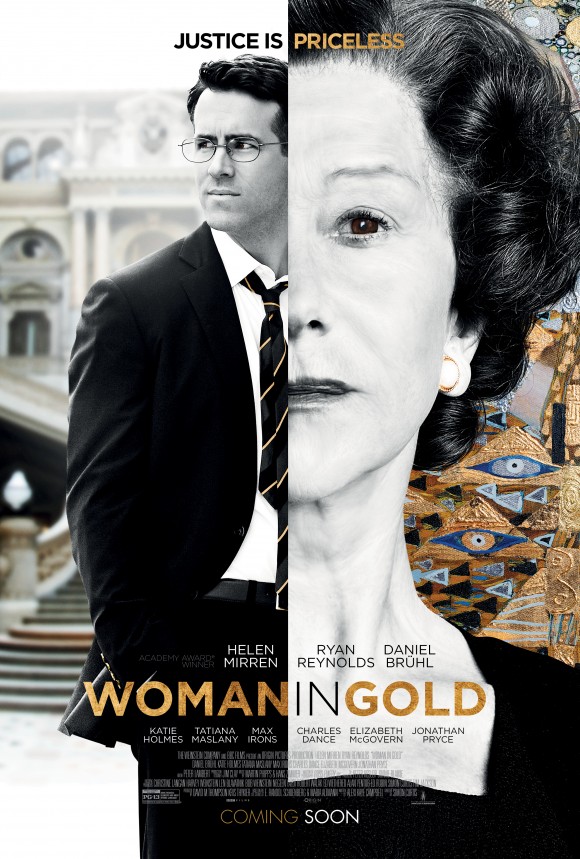

On Thursday, September 10, in Memorial Auditorium, the Rodgers Center begins its fall series of events with a screening of

Woman in Gold

starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds. Later in the semester, on October 13, we will be privileged to have with us the real life attorney played by Reynolds, E. Randol Schoenberg, to describe the case and his pursuit of justice on behalf of his client, Maria Altmann. The film powerfully represents our themes for this year:

memory, meaning, and justice

.

A bit of background: In fin-de-siècle Vienna, Ferdinand and Adele Bloch-Bauer lived a prosperous and elegant life. Their home was a gathering place for many of Vienna’s most renowned artists, writers, composers and political figures. The Bloch-Bauers were immense supporters of the arts and amassed an extraordinary collection, including paintings and an unrivaled collection of classical Viennese porcelain. Their two most spectacular works of art were the portraits of Adele commissioned by Ferdinand and painted by the most famous Viennese artist of the time, Gustav Klimt.

In 1925, Adele passed away suddenly at age 43 from meningitis, but Ferdinand was still living in their palatial home on Elisabethstrasse when the Germans marched into Vienna and annexed Austria in March 1938. Ferdinand fled soon thereafter, first to Prague and then to Zurich. Through bogus claims of unpaid taxes, Nazi bureaucrats robbed Ferdinand and his family of his sugar factory and his wealth, his treasured porcelain collection, and his paintings, including the two Klimt portraits of his beloved wife.

This story with its web of injustices during both the Nazi and the post-war era is not unique. The bureaucratic intransigence, antisemitism, and sheer greed by which those who had profited from Jewish persecution sought to retain their ill-gotten gain played out throughout Germany, Austria, and beyond. Few survivors or families of survivors were fortunate to have as brilliant and indefatigable an advocate as Maria Altmann had in Randy Schoenberg, the grandson of exiled composers Arnold Schoenberg and Eric Zeisl. For him the quest for justice was a deeply personal one.

What the Nazis did to the Bloch-Bauers might well be called property theft. In reality, however, their theft went beyond property. The museum officials who took the Klimt paintings for the Austrian state gallery, the Belvedere, knew who Adele was. They knew she was a Jew. They also knew the painting was one of Klimt’s greatest works, and so they chose to exhibit the stunning golden portrait but hide the name of Klimt’s subject. Quite simply they stole Adele’s identity. The theft extended into the post-war era as the painting continued to be exhibited as “The Lady in Gold.” Indeed, the painting became a special focus of Austrian national pride and the symbol of the extraordinary accomplishments of its golden age. Some spoke of the painting as the

Mona Lisa

of Austria.

For Maria Altmann, the painting was a family legacy, part of the inheritance willed to her and her siblings by her uncle, Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer. She sought the restitution of what had been stolen by the Nazis, and she sought something else, restitution of a different sort. The world should again know Klimt’s spectacular painting by its true name, not as the anonymous “Lady in Gold” but as a person with a history who was loved and remembered. Maria Altmann’s quest became the restitution of the painting’s stolen identity,

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer

.