Why the Word ‘Genocide’ Matters Recognizing the Armenian Genocide

April 27, 2021

Marilyn J. Harran

Professor of Religious Studies and History

Stern Chair in Holocaust Education

Chapman University

On Saturday, April 24, for the first time, a U.S. president officially referred to the mass murder of Armenians during World War I as “genocide.” To say the statement was long overdue is a huge understatement. Indeed, it is generations overdue. The long delay has been an exceptionally painful experience for Armenian Americans, a great many of whom live in Southern California. We have been privileged over the last several years at Chapman University to have one of the foremost historians of Armenia and the Armenian genocide, Dr. Richard Hovannisian, as a Presidential Fellow. He speaks often of growing up in the farming community of Turlock surrounded by survivors of the genocide. Indeed, his own father, just a boy at the time, was rescued from a death march by an Arab trader who took him as a forced laborer. That less than noble act saved his life. Eventually his father escaped and made his way to the United States. It is thanks to Professor Hovannisian, for whom the chair in modern Armenian history at UCLA is now named, that the voices of some survivors of the Armenian genocide were recorded and now are part of the collection of oral histories at the USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive.

Holocaust survivors faced innumerable challenges as they tried to move forward with their lives after World War II while also honoring the memory of the family members and friends murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. But with the exception of those misguided individuals and groups still obsessed with Holocaust denial and distortion, survivors did not have to fight to have what they experienced recognized for what it was, namely genocide, the planned effort to eradicate an entire people, even though today they are witnessing an alarming rise in antisemitism around the world. Armenian Americans, in contrast, were disappointed year after year as one U.S. president after another failed to refer to what had occurred as genocide. That disappointment was especially acute when President Obama, who had promised during his first presidential campaign to use the word “genocide,” did not do so. At each year’s memorial ceremonies, U.S. administrations once again prioritized military and strategic needs, along with preserving cordial diplomatic relations with Turkey, ahead of calling what occurred to the Armenians by its true name—genocide.

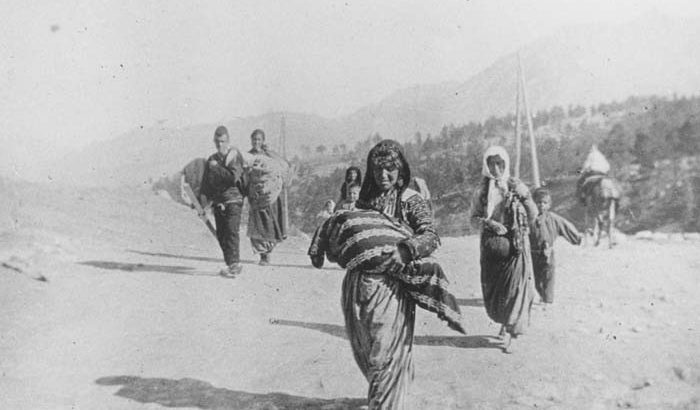

A bit of background: On April 24, 1915, Turkish authorities rounded up and ultimately executed some 200 or more Armenian public and community leaders, including intellectuals, businessmen and artists. That action would soon be followed by the mass murder of Armenian men and the deportation by train or forced marches of women and children to the Syrian desert. There was widespread brutality and sexual violence, along with a great number of deaths from starvation, dehydration or exhaustion. By 1923, approximately 1.5 million Armenians had died and a rich Armenian culture and history in large part eradicated.

One might ask why it matters so much, not only to Armenians and those of Armenian background, but to all of us, that these events be termed genocide. The term “genocide” had not yet been coined at the time of the First World War. It was created in 1944 by Polish Jewish legal scholar Raphael Lemkin who escaped Europe for the United States after Germany invaded his native Poland. Lemkin defined genocide in this way: “By ‘genocide’ we mean the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group. This new word, coined by the author to denote an old practice in its modern development, is made from the ancient Greek word genos (race, tribe) and the Latin cide (killing).” In other words, what occurred from 1915-1923 should not be mislabeled or misunderstood as civilian casualties during wartime, but instead seen as the planned effort to eradicate an entire people. Armenians did not die by chance but by plan, and the Turks used the latest technology of the time, the telegraph and railroad, for instance, to implement their plan.

Adolf Hitler is alleged to have said in a 1939 speech “who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?” His point was that it is often the perpetrators not the victims who control the historical narrative. He also, of course, learned from the Armenian genocide that under the cover of war, it is possible to wage genocide as a “war within a war.” What was happening to the Armenians was no secret at the time, even as war was being waged. Henry Morgenthau, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire from 1913-1916 received multiple reports from his consuls throughout the empire, as well as from missionaries and journalists, describing what they had witnessed, including deportations. He forwarded those cables to the State Department, but the U.S. was intent on maintaining its neutrality in the war. It is one of history’s many ironies, that it was Morgenthau’s son, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., who as Secretary of the Treasury in the administration of FDR, would play a vital role in advocating for the War Refugee Board. While U.S. policy prioritized winning the war over rescuing Jews, under the leadership of John Pehle, the War Refugee Board, working with the American Jewish Joint Committee, would ultimately save tens of thousands from genocide.

Officially recognizing what occurred to the Armenians as genocide is a first step, not a final one. At least, it means that the perpetrators and those who perpetuate their legacy do not get to keep rewriting history to suit their aims. It may also mean that instead of continuing the battle for recognition of these events as genocide, we can instead focus on what we can learn from them to prevent such acts in the future. That might well be the greatest and most meaningful tribute to all those murdered in the Armenian genocide.

Image of Armenian deportees courtesy of Sybil Stevens (daughter of Armin T. Wegner). Wegner Collection, Deutsches Literaturarchiv, Marbach & United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Image of Armenian refugee woman courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Photothèque CICR (DR) / s.n.