Sharing Korean Cinema Across the World Faculty Spotlight: Dr. Nam Lee

May 19, 2022

Associate Professor Dr. Nam Lee.

In honor of Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Dodge College is proud to celebrate our very own Dr. Nam Lee. Hailing from Seoul, Korea, Dr. Lee is an associate professor at Dodge College with expertise in Film Studies, Korean Cinema, Asian Cinema, Women’s Filmmaking, and Transitional Cinema. As a teacher of film studies, Dr. Lee exposes students to the works of filmmakers from around the world.

We were lucky enough to hear from Dr. Lee on the influence of Korean Cinema in her own life and career, as well as her time teaching here at Dodge College:

How did Korean Cinema influence your decision to pursue a career in film studies?

I grew up in Seoul, South Korea, so Korean cinema has always been part of my life. I remember watching Korean films on TV with my family, but I have to say, we watched more Hollywood films than Korean films. My father liked to watch John Wayne westerns (but my favorite was Shane), and my mother loved Hollywood melodramas (Waterloo Bridge and Love is a Many-Splendoured Thing were her favorites). Korean cinema enjoyed its Golden Age in the 1960s; however, during the 1970s and 1980s, Korean films’ quantity and quality declined sharply due to the harsh censorship under the draconian military dictatorship. These two decades were dark times for the Korean film industry.

In the late 1980s, the Korean people achieved political democracy after the June Uprising in 1987. Film censorship was abolished in 1993. A new generation of Korean filmmakers emerged with this newly found creative freedom. However, the 1990s was also a decade during which Korean cinema faced a new crisis: competition with Hollywood. Hollywood Studios began to distribute their films, thus, depriving Korean distributors of any box office revenue. The US also urged the Korean government to eliminate the Screen Quota system, a protection system for domestic films, by guaranteeing that each screen shows a Korean film for a certain number of days per year. Korean cinema’s domestic market share fell to an all-time low of 15.3%. This crisis stimulated the young filmmakers to devise various ways to compete with Hollywood domination, and the New Korean Cinema succeeded in winning back the Korean audience from Hollywood films.

I was a print journalist and a film critic before I came to the US to earn a PhD in Critical Studies at the School of Cinematic Arts, USC. I left Korea when the new generation of filmmakers and critics actively sought ways to make new films that would appeal to the Korean audience and rediscover classical movies. I also belong to this generation who grew up mainly watching Hollywood films but became newly interested in studying the history of Korean cinema. When I came to the US in 2000, most American audiences did not know about Korean cinema, even though Hollywood studios were actively acquiring remake rights for Korean films. In 2022, my interest in Korean cinema has grown exponentially on a global scale, and I am really happy to teach Korean cinema at Chapman.

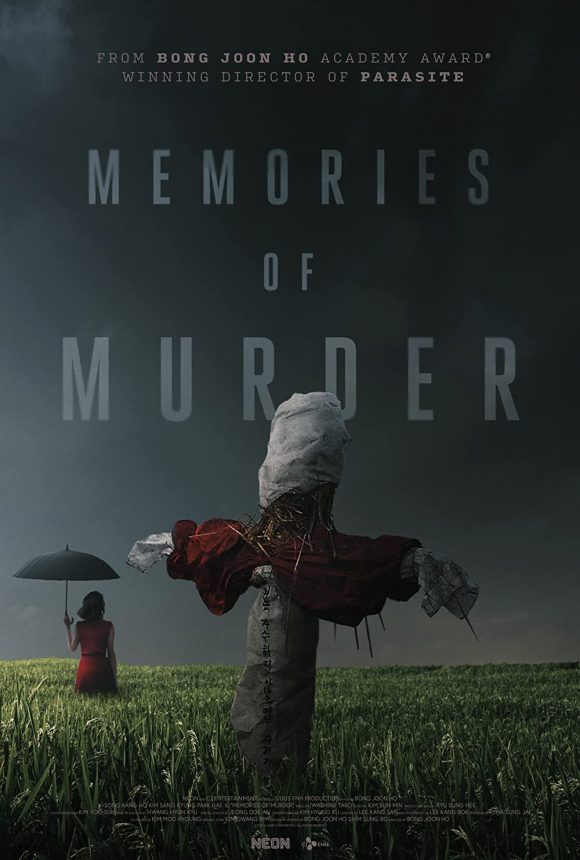

Bong Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder (2003).

What is one Korean film that you think everyone should watch?

This is a tough question. But if I have to choose one, I would say Bong Joon Ho’s Memories of Murder (2003). It is a crime thriller based on an actual serial killer case that shook the whole nation in the 1980s. The case remained unsolved at the time of its production. So the Korean audience knew that the two detectives, the protagonists of the film, would fail to capture the killer in the end. Although audiences already knew the story’s outcome, the film successfully maintains the narrative tension till the end. It does so by making the film, not about the killer but the 1980s Korea. It focuses on why the two detectives failed. It points to the military dictatorship that mobilized the police force not to protect ordinary citizens but to protect itself from massive demonstrations against the military dictatorship. A failed investigation is a risky subject for a commercial film, but Memories of Murder was a smash hit when it was released. It is also the only film made in the 21st century to be included in the all-time top 10 best Korean films ranked by the Korean Film Archive.

Why is it important for students to be exposed to cinema from different cultures?

According to the Korean Film Council’s statistics, the domestic film market share in the US has consistently been above 90% in the 21st century. The latest 2019 share was 92.5%. This means that of all the films released in the US, 92.5% are American films. This means that hundreds of movies produced every year outside of the US go unnoticed by the American audience. We are missing so much of film history if we only watch Hollywood movies. Watching and learning about cinemas from different cultures is crucial because it is all part of cinema’s history. If you have studied film history, you will know that cinema has been an international art or entertainment form from the very beginning. Hollywood’s way of filmmaking is the most dominant but not the only one. Many new wave cinemas or new cinemas worldwide have developed different filmmaking traditions from different perspectives. Cinema is the best way to understand people of other cultures as well as to be inspired by different thoughts and ideas behind different traditions of filmmaking. Films from different cultures will broaden your world of imagination and allows you to develop empathy towards others. Therefore, watching films from different cultures is an ethical imperative.

What has been the best lesson that you have learned from your students?

The best lesson I have learned from my students is the passion for pursuing their dream and being proactive in making things happen. I get a lot of energy from their optimistic vibe.

What advice would you give to Asian and Pacific Islander students pursuing a career in the film industry?

We see changes happening with more mainstream films that feature Asian characters as protagonists. However, most Asian representations often do not recognize the diversity present in the Asian community. Many recent Asian-related films focus on East Asians and not so much on South Asian or Pacific Islanders. So there still are efforts to be made. My heartfelt advice to Asian and Pacific Islanders students pursuing a career in the film industry is not to be discouraged by the hardship, difficulties, and disappointments you experience along the way. Changes come slowly but surely if you persist and follow your heart. Reach out to Asian and Pacific Islanders communities within the film industry to connect and encourage each other; if there isn’t one, make one.

In what areas of Dodge College do you see room for improvement in diversity and inclusion?

Many initiatives and changes have been brought to Dodge College regarding diversity and inclusion. We are looking at the ways in which courses can incorporate DEI in their syllabi. We are also discussing different ways to internationalize our program. I think some improvement that can be made in Dodge College and at Chapman as a whole would be encouraging students to learn a second language. Atom Egoyan, the Canadian director who has edited a book titled, Subtitles: On the Foreignness of Film (2004), talks about how American film culture is monolingual. The best way to learn about other cultures and people is to learn their language. And I believe that being in an environment where you have to communicate in your non-native language opens you up to others in a more profound way.