In Complex Care Settings, Fong Prepares Students to Expect the Unexpected

July 15, 2025

At Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, one of California’s largest safety-net hospitals, patients navigate medical complexities while also facing difficult realities like unstable housing, limited income, low health literacy, and living with chronic conditions that often go untreated for years. These challenges ask healthcare providers to think creatively and compassionately about how to provide specialized care, including Gary Fong, Pharm.D., a clinical preceptor and Assistant Professor at Chapman University who practices in infectious diseases. To Fong, the challenges patients face present an opportunity to teach future pharmacists how to provide compassionate, safe, and patient-centric care.

At Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, one of California’s largest safety-net hospitals, patients navigate medical complexities while also facing difficult realities like unstable housing, limited income, low health literacy, and living with chronic conditions that often go untreated for years. These challenges ask healthcare providers to think creatively and compassionately about how to provide specialized care, including Gary Fong, Pharm.D., a clinical preceptor and Assistant Professor at Chapman University who practices in infectious diseases. To Fong, the challenges patients face present an opportunity to teach future pharmacists how to provide compassionate, safe, and patient-centric care.

“As a safety net county hospital, a significant portion of our patients are of low socioeconomic status, have low health literacy, and/or are resource-limited,” explains Fong. “These factors make them more susceptible to both common and more severe infections, and also make standardized approaches to care far more complex.”

Fong brings his experiences and stories from Harbor into CUSP’s classrooms, where he is the primary instructor for both Infectious Diseases I and Applied Pharmacokinetics. Each course bridges CUSP’s exceptional teaching with the lived experiences of underserved patient populations.

In Infectious Diseases I, Pharm.D. candidates explore the science behind antibiotics and treating conditions such as skin infections and pneumonias. These are diseases that are very common across most populations, including patients Fong serves at Harbor. “We intentionally spend time talking about how to make antibiotic selections that work for patients beyond efficacy and safety,” he says. “We ask, can they take it two times a day with food? Does it require refrigeration? These are limitations care professionals don’t routinely consider for all patient populations.”

In Infectious Diseases I, Pharm.D. candidates explore the science behind antibiotics and treating conditions such as skin infections and pneumonias. These are diseases that are very common across most populations, including patients Fong serves at Harbor. “We intentionally spend time talking about how to make antibiotic selections that work for patients beyond efficacy and safety,” he says. “We ask, can they take it two times a day with food? Does it require refrigeration? These are limitations care professionals don’t routinely consider for all patient populations.”

Applied Pharmacokinetics informs students how to tailor doses using clinical parameters such as kidney function and weight. “At Harbor, we have a significant number of patients who are overweight and/or have chronic kidney disease. We also have a large patient population with varying degrees of amputation from diabetes-related complications or who are para- or quadriplegic from trauma like gunshot wounds. All of these factors, in addition to living situation and resources, mean a patient’s dosing regimen may not follow a standard template.”

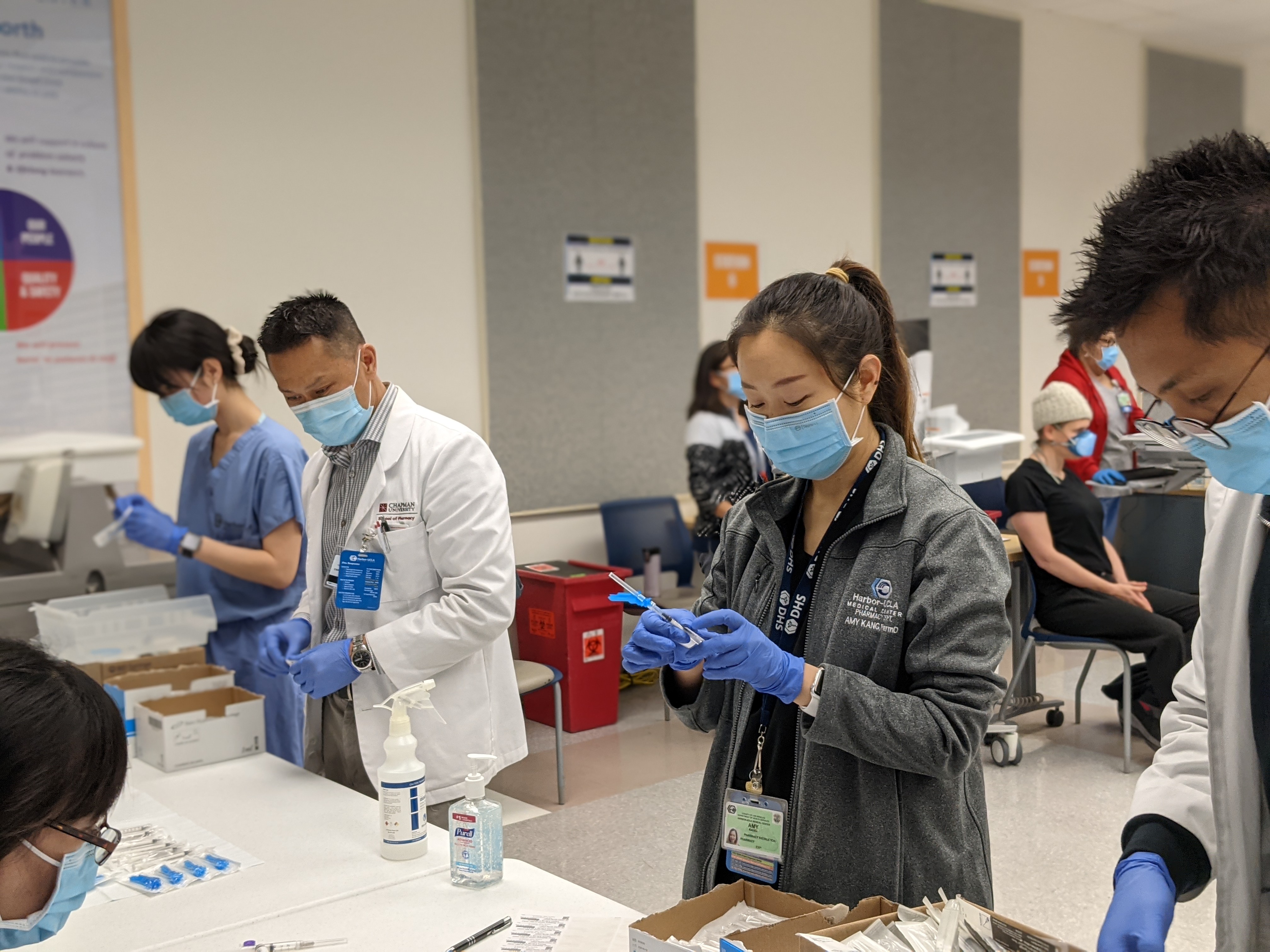

During their third and final year, Pharm.D. students can put these lessons into practice by spending one of their six, six-week-long APPE rotations at Harbor. At Harbor, they may gain experience in ICU, neurology, infectious diseases, immunocompromised services, and other departments relevant to patient populations served at safety-net hospitals.

“Students typically work with patients on their own in the morning, then discuss their patients with me and the other preceptors before going on patient care rounds with the team. These rounds may take one to three hours daily. After our rounds, we debrief with our students and then follow up on needed items or questions asked by the team. We give students significant independence to develop confidence and clinical reasoning.”

Independent thinking is especially important in safety-net hospitals, where best-practice care often means thinking beyond standard clinical guidelines.

Independent thinking is especially important in safety-net hospitals, where best-practice care often means thinking beyond standard clinical guidelines.

“When a patient is discharged, it is our responsibility to come up with a treatment plan that works for the patient, not one that just works for us,” Fong explains. “For patients who do not have stable housing, we have to consider avoiding medications that require refrigeration or any special storage requirements. In selecting treatments, we need to be cognizant of the patient’s insurance situation and how that impacts the affordability of medications. Patients are more likely to decline rather than advocate for themselves and ask for an alternative.”

Cultural awareness is also essential. “A majority of our patients do not speak English as their first language, and many come from regions where infections often considered uncommon in the United States may be more common,” Fong describes. “Patients also may use home remedies that affect how we prescribe. We have to adapt to their practices and must be extra diligent if prescribing a medication that requires more extensive counseling.”

From an instructor’s perspective, Fong sees the complexities as a valuable training opportunity.

“Working at Harbor is fulfilling because there is a sense that you are doing your best for patients who need it the most. The impact that your care can have on these patients is often life-changing. And for our students, that’s where their growth happens. They don’t learn what’s just clinically correct, but learn how to care for people with real constraints.”

As Fong teaches students how to interpret and care for different, unique situations, he also faces a misconception in healthcare.

“There is often an assumption that the best treatment is the one most backed by evidence,” he says. “But we need to ask, what’s the ‘best’ for this patient, in this situation? It is not always the best idea to make a patient change their life so that it works for a first-line treatment plan, but instead, we should be critically evaluating the literature to see if an alternative option may be just as effective, given the circumstances. The best medication is the one that the patient can actually take.”

Through both his teaching at Chapman University and his clinical leadership at Harbor-UCLA, Fong is nurturing the next generation of pharmacists to think critically about each individual patient, one dose at a time. Are you interested in earning your Pharm.D. with Chapman University? Click here to learn more about our degree options.