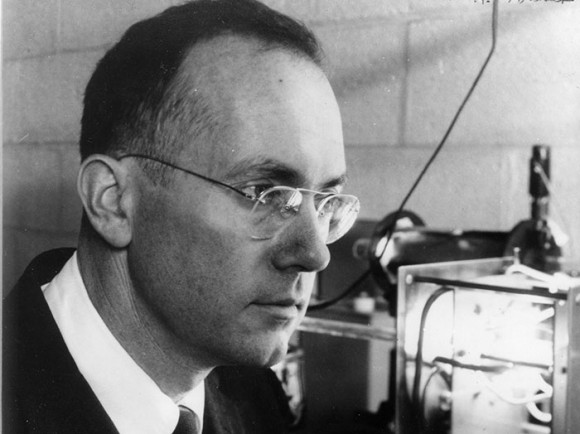

The Inventor of the Laser Leaves a Legacy of Brilliance

January 29, 2015

Dr. Charles H. Townes’ genius will forever influence the technologies of the world. He won the Nobel Prize in physics for his invention of the laser in 1964 and continued to create numerous technologies driving our economy today. By improving modern surgery, medical devices, computer processing and much more, Townes paved a way for science and discovery. Many may want to follow his example, but is it more than a person’s intellectual brilliance that can change the world?

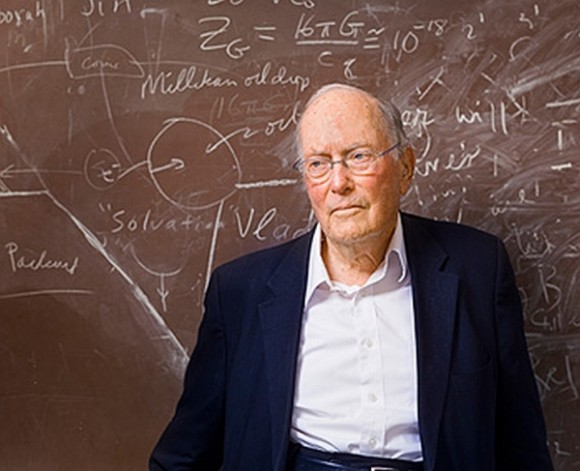

Jeff Tollaksen,

Ph.D.,

Chapman professor and director of the Institute for Quantum Studies

, thinks so.

Amid white boards covered in mathematical equations and books stacked high, Tollaksen reminisces on the good times he had with his world-renown colleague, whose death January 27 marked the end of an era.

Tollaksen first met Charles “Charlie” Townes at a 1992 conference held in honor of

Yakir Anaronov, Ph.D.,

current

Chapman professor

and winner of the

the National Medal of Science in 2009

. The conference was attended by the most famous physicists in the world, including five Nobel laureates.

At the conference, Townes enjoyed deep discussions with John Wheeler, Ph.D., who was a colleague of Einstein at Princeton. Both Townes and Wheeler were influential in building U.S. defense and protection technologies at the time.

“It was clear that the two of them urgently needed some private time, away from the conference,” Tollaksen says. “Nevertheless, Charlie and John Wheeler stopped what they were doing and took quite some time to talk to me. In spite of all these other urgent pressures on Townes and Wheeler, they both became like students, even younger than me and brimming with curiosity, and dove into an inspirational discussion with me about the research I was doing.”

Tollaksen was a graduate student working toward his Ph.D. with Aharonov at MIT and Boston University. The impact Townes and Wheeler had on Tollaksen that night and in future interactions went beyond the formalities of science and research.

“They were both such gentlemen,” Tollaksen says. “These are physicists that every scientist idolized as heroes as they were growing up. …. Even to this day I feel can remember much of what they said to me during these one-on-one interactions. And that set the content for all the other interactions that we had. They had this enormous humility and generosity of spirit.”

With Townes’ generosity of spirit came his willingness to exchange ideas, seek truth and make the greatest impact serving the most. Townes served as chairman of many science-related government commissions, including the Apollo NASA missions. He also advised President Reagan on controls for the MX nuclear-tipped missiles.

Four members of Chapman’s Institute for Quantum Studies work with Townes on a chapter of Townes’ book “Visions of Discovery”. This chapter was contributed by Aharonov and Tollaksen. From left-to right: Paul Davies, Yakir Aharonov, Charlie Townes, Jeff Tollaksen, Sandu Popescu.

Tollaksen remembers Townes as a peaceful person, even when he was fervently searching for answers.

“When they are trying to solve a new and big problem, scientists have different styles and approaches,” Tollaksen says. “For example, some scientists become aggressive. You can tell they are sweating, stressed out. But it seemed like Charlie was always having fun, playing with the problem like he was still a kid. In my opinion, when you can get into that mode of just enjoying it, that’s when you become most creative. But, when you are not playing, you know, not having a sense of awe and respect for the grandeur of the universe, you often shut down an aspect of your creativity.”

Townes also lived a life dedicated to charity and faith. He was an avid member of the First Congregational Church of Berkeley and a pioneer in exploring the link between faith and science. In 1966, he published a daring article in the IBM journal

THINK

titled

The Convergence of Science and Religion

. The article contributed to his winning the

Templeton Prize in 2005

. Townes would share the $1.5 million prize with Furman University and church-based charities.

Throughout his groundbreaking career, Dr. Charles H. Townes demonstrated how to maintain a sense of awe and discovery, to thrive joyously, and to change the world. He continues to inspire his scientific colleagues, including one who met him as a graduate student and came to treasure his friendship.

“His brilliance of heart,’ Tollaksen adds, ‘not just his brilliance of mind, is what stays with me like a companion to explore the subtleties of this universe. We can all learn how the power of joy, authentic friendship and disciplined thinking invites our highest creativity to find the very edge of discovery.”