Dean’s Diversion: Summer Reading List

June 14, 2015

Towards the end of this past spring semester, I walked into my office to find the dreaded red “you have voice mail” light blazing on my phone. As I listened to the message, I was happy to hear the voice of President Doti, who is known to use the medium to broadcast his musings to the entire campus. This time, he was sharing a summer reading list – suggestions for us to all consume as things wind down over the summer.

Not to be too derivative, I thought I might offer my own spin on this. I seem to recall that the president was fond of a nice mix of biographical, historical, and fiction pieces. I am much more drab, and tend to lean towards non-fiction almost exclusively these days. I am so boring that the books I thought of sharing have essentially the same cover color schemes – eye-catching, no?

Nonetheless, I do think that the readers of a science blog might be a good audience for these four volumes; each of them is a relatively easy read (at least when compared with an

Umberto Eco

novel), so don’t be put off by the subject matter.

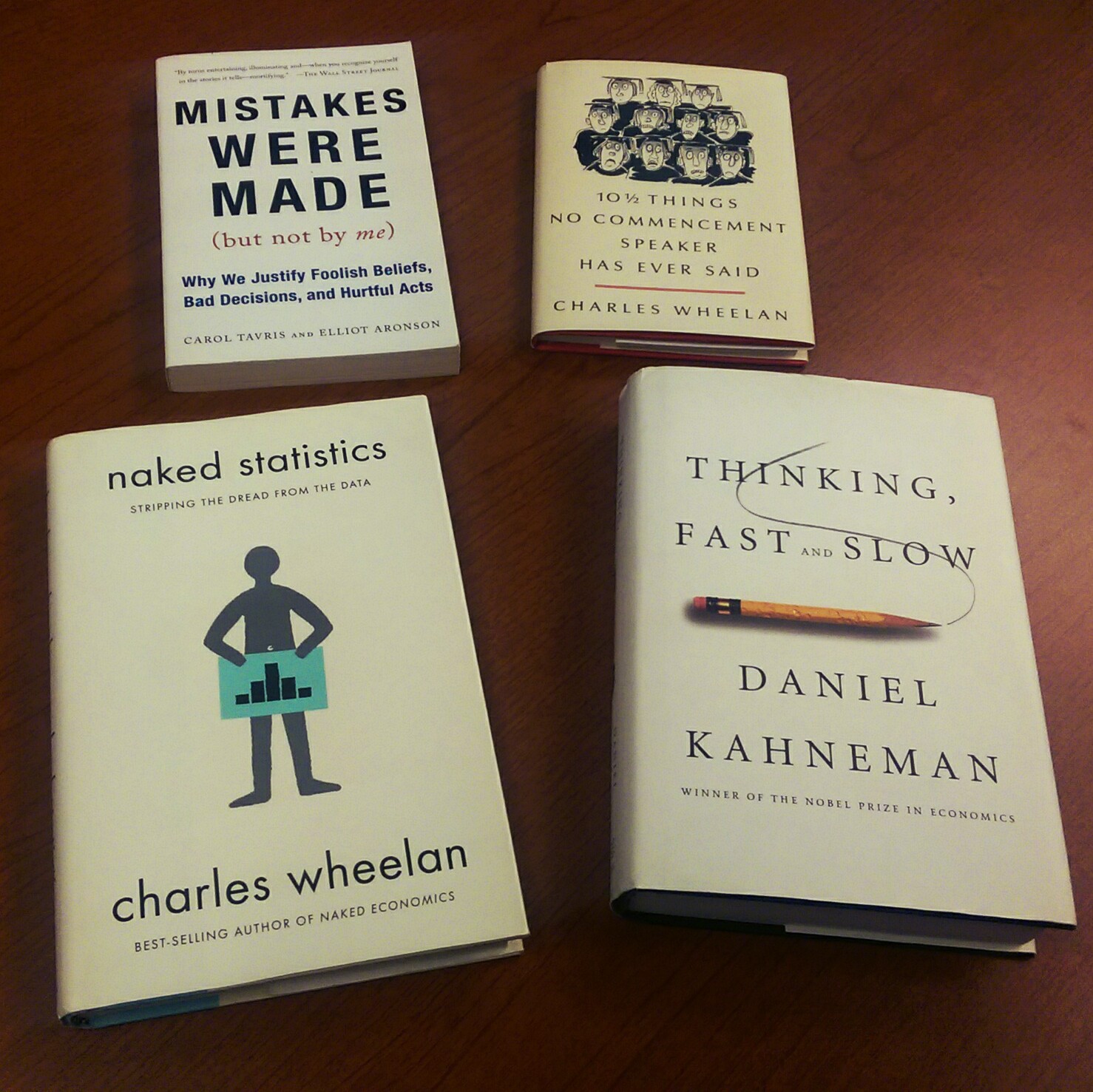

Mistakes Were Made (but not by me)

First up is

Mistakes Were Made (but not by me)

by Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson. Here, the authors take us through the world of

cognitive dissonance

. They recount an often-unbelievable set of stories describing the lengths people will go to in rationalizing their beliefs with contrary sets of data, evidence, and experiences. This is a great read for anyone involved in science, as it reminds us to be self-critical, cautious, and unbiased as we move from observations to explanations and conclusions. Additionally, it delves into the psychology of why it is so painful to arrive at a conclusion that differs from a strongly held belief, and why one might go to extraordinary lengths to avoid or alleviate that psychological pain.

10 ½ Things No Commencement Speaker Has Ever Said

The second pick is a much shorter and lighter read, and the first of two picks from

Charles Wheelan

. I’m a big fan of Wheelan’s writing, so I couldn’t resist plugging a couple of his works. In

10 ½ Things No Commencement Speaker Has Ever Said

, Wheelan retells and recounts a (not) commencement speech he gave to graduating seniors at Dartmouth in 2011. The brilliance of this book comes from Wheelan’s honesty; he provides advice to the soon-to-graduate that runs wonderfully contrary to the intense environment of academic overachievement in which we currently live. Just a quick glance down the table of contents immediately tells you what he is going for:

Number 1: Your time in fraternity basements was well spent.

Number 3: Don’t make the world worse.

Number 7 ½: Your parents don’t want what is best for you.

Number 10 ½: Don’t try to be great.

You get the picture – you need to read the book to find out what he

really

means by all of this.

Naked Statistics

My other Wheelan suggestion is a bit denser, but only slightly so.

Naked Statistics

is not a voyeuristic look into the seedy underbelly of academic math departments, but rather a primer on the actual meaning of various bits of arcane statistical jargon. He then moves from the terminology and concepts to a wonderful series of examples where stats can help us understand extraordinarily important things like “Chapter 4: How does Netflix know what movies I like?” or “Chapter 6: How overconfident math geeks nearly destroyed the global financial system.” Overall, the reader comes away with a better appreciation of how numbers can be manipulated for good, evil, and sometimes entertaining purposes.

Thinking, Fast and Slow

Finally, we come to the most challenging, but also the most rewarding of the four reads.

Thinking, Fast and Slow

by Nobel Laureate

Daniel Kahneman

(

Economic Sciences, 2002

; shared with Chapman’s own

Vernon Smith

) discusses the two modes of thought that most (all?) people possess. Fast, reactionary responses are governed by intuition, while slow, methodical approaches are typically viewed as “thoughtful” or “analytical”. As scientists, we often take pride in our constant use of the slow channel. We carefully and analytically break down our arguments, turn them inside out, and then reassemble them to ensure that they are robust, defensible, and ready for vetting by the scientific community. However, it is often the case that we do use our intuition and fast thinking to jump directly from data to inference without going down the rabbit hole associated with truly exhaustive experimentation. Without that fast thinking, we might never move forward to the breakthroughs, advances, and paradigm shifts in our thinking that make being a scientist so compelling and exciting. It remains our job to balance these two thought channels carefully and responsibly – to not get fooled by faulty intuition while not getting bogged down by the fear of being “wrong”.

Anyway, I hope you have a chance to take a look at one or more of these over the summer – they may not be the guilty pleasure diversions you are looking for, but you just might do even more fantastic science after reading them.