Getting a Taste of What it Means to be a Professional Ecologist A tale of summer research in Panama

September 1, 2016

An Aplysia inking for self-defense.

This summer, I went on a fantastic adventure. I adventured to a faraway land, where the natives speak in a foreign tongue, the drivers do not understand the concept of yielding at a roundabout, and June is smack in the middle of the rainy season. I traveled, with my professor, Dr. William Wright, to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute outside of Panama City, Panama.

Learning about Learning

Why did we journey to this new environment?

A research project that has been bouncing around in Dr. Wright’s lab for years had recently landed on my plate. We are investigating a peculiar species of sea hare, Dolabrifera dolabrifera, who have mysteriously lost the otherwise ubiquitous ability to learn from a painful experience. Other species of sea hares will increase their defensive withdrawal reflexes in the minutes, hours and even days following a painful episode, but not our Dolabrifera.

Dolabrifera grazing on the floor of a tide pool

Why do sea hares need to learn from a noxious stimuli? Is it important to their survival? We think it must help sea hares survive, because all but Dolabrifera can do it. Then how in the world might losing this ability to learn be adaptive? How did Dolabrifera evolve away the ability to learn.

Most people, myself included, think that learning is a great thing to do. Learning makes us better equipped to handle the uncertain situations of the future. Presumably, sea hares work the same way. It is our current belief that these creatures increase their defensive withdrawal after painful experiences so that next time they are harmed, they can better protect themselves and nurse their injuries.

Given that belief, Dolabrifera are the exception to the rule. They don’t learn from predator attacks, or other painful experiences like getting hit by waves or rocks in the rough intertidal, so Dr. Wright and I went to Panama to figure out how they can possibly survive in the dangerous intertidal region of the beach without this seemingly important learning pathway.

A Flurry of Hypotheses in Panama

Dr. Wright and I arrived in Panama on the night of June 19th, got all squared away in our hotel, called The Beach House, got a nice dinner of corvina and arroz con coco (the local fish and coconut rice) at Mi Ranchito (which quickly became our favorite restaurant), and went to bed, eager to start working the next day.

Panama began as a flurry of creating hypotheses, drawing up creative means of testing them, and working for hours in the scorching sun, pouring rain, and even thunder at all hours of day and night in the field to record data. Our initial observations of Dolabrifera showed that they only emerge from crevices and under boulders during daytime low tide. We hypothesized that Dolabrifera don’t need to learn because they simply hide from danger; therefore, both nighttime and high tides must be too dangerous for them because predators are on the prowl and waves can damage the Dolabrifera.

- The beach next to our study site.

- A daytime high tide in the intertidal where Dolabrifera live.

- A daytime low tide in the intertidal where Dolabrifera live.

Our most promising data came from painstakingly careful monitoring of Dolabrifera movement in the tide pools. We quantified that Dolabrifera remain in protective hiding until moments after their pool is fully uncovered as the tide goes out. Then, they forage for a few hours or until night falls, when they return to their protective crevices. The Dolabrifera additionally showed a striking aversion to dusk; even in the waning tide (which is when the sea hares usually emerge), not one single Dolabrifera would come out of hiding to graze if night was falling. This data is an excellent indicator that they are terribly afraid of the night and high tide, which indicates that predatory pressure could force them into hiding.

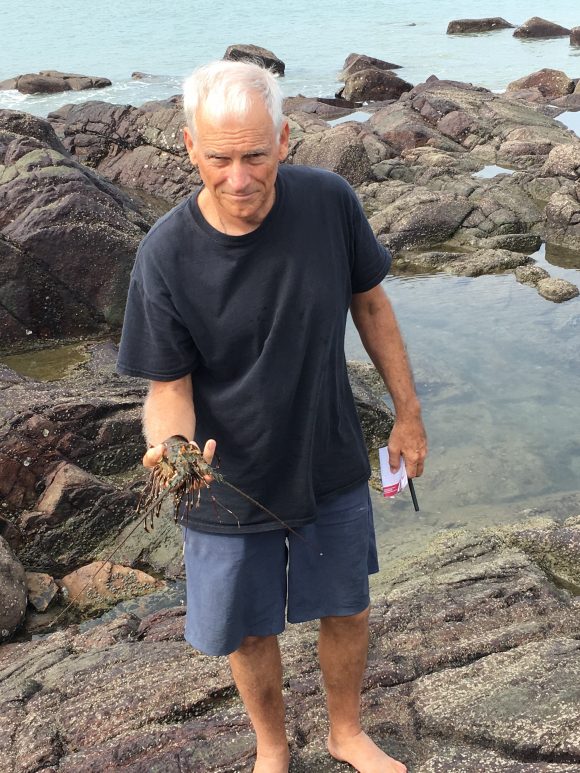

Dr. Wright with a lobster carcass. We expected to see crustaceans predate on Dolabrifera.

Working Day and Night, Looking (at Tides) High and Low

Dr. Wright and I worked feverishly to find a Dolabrifera predator both at night and during high tides. We fashioned bottle traps out of plastic bottles and fishing line, which we baited with fish carcass, and we caught a myriad of aquatic species. Unfortunately, none of the species ate Dolabrifera when we presented one to them.

Discouraged, but unwilling to give up, we tethered Dolabrifera to fishing weights using fishing line in shallow tide pools during nighttime low tides, but none were eaten. We even set up a GoPro video camera to monitor their movement during two of these tethering experiments, but we failed to find a possible predator.

What initially appears to be a Gatorade bottle is actually a makeshift fishing rod!!!

Finally, Dr. Wright and I fashioned makeshift fishing “rods” out of Gatorade bottles, fishing line, weights and hooks, where the Gatorade bottle served as the reel. We fished the incoming tide, and were able to catch two large fish of the same species. Unfortunately, our fish responded ambivalently to the presence of the Dolabrifera we presented to them. We are still at a loss for what could possibly eat Dolabrifera, but we did gain vital knowledge about these peculiar species which can survive without sensitization. They don’t need to learn because they only emerge from hiding under the safest of circumstances: daytime low tides.

I had an incredible experience in Panama, and I got a taste of what it means to be a professional ecologist. Dr. Wright and I spent over 6 hours clambering over slippery rocks, counting Dolabrifera, setting traps or fishing in the rocky intertidal each day. We lived according to the schedule of the tides, often venturing out at 2, 3, 5 or 6 am to check traps, or count the animals in each tide pool. Weather did not prevent us from collecting data, and I have never felt so alive as I did scampering over slimy rocks while rain smacked my skin and lightening cracked over the water.

In Panama, I got a better sense of what it means to be a behavioral ecologist in the field, and I loved every minute.