The Bones in the Back Room Summer discoveries unearth ancient history in Jack Horner's Dino Lab

November 14, 2025

Amid ancient bones and the sounds of picks scraping stone, Professor Jack Horner and his team are hard at work in Chapman’s Dino Lab.

In the back of Hashinger Science Center, students are preparing dinosaur bones for display. The Dino Lab, founded and run by Professor Jack Horner, is full of fossils of all shapes and sizes. Tiny fragments and impressions of prehistoric leaves line shelves and a roughly two-foot-long leg bone lies on a table. Students in the Dino Lab painstakingly stabilize and clean fossils, removing excess stone to reveal the bones underneath. Chapman does not have a specialized course of study for paleontology, so Horner made a place for students to explore the discipline outside of classes.

“I want the students to be exposed to every aspect of paleontology, so I give them as much leeway as I can to do everything, no matter what their major is,” says Horner.

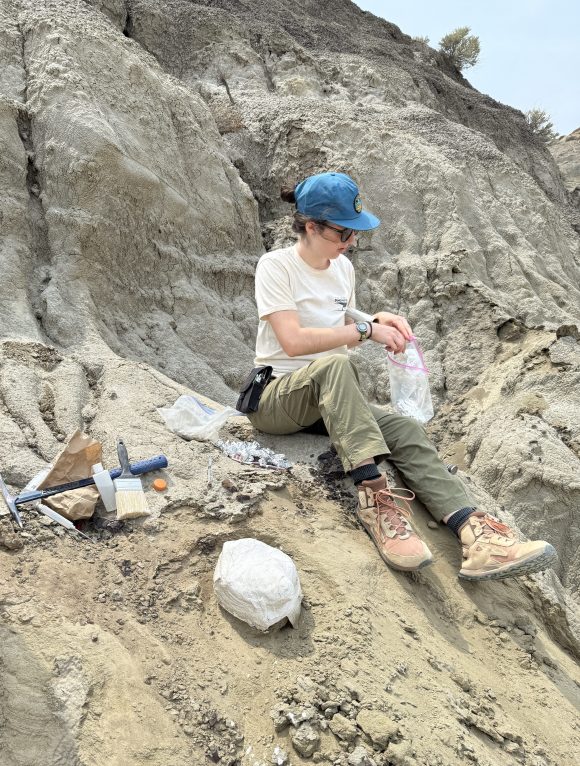

Lab Manager Greta Kunze ’26 hard at work at one of the dig sites. (Photo courtesy of Greta Kunze)

Horner is known across the world for both his discoveries in paleontology, and for his consulting work on the Jurassic Park films. He is the only Schmid College professor without a Ph.D., or any formal degree in the sciences, and teaches within the Honors College as a Presidential Fellow. He also leads research at the Dino Lab, mentoring students interested in paleontology.

Greta Kunze ’26, the student lab manager, says that Horner takes a hands-on approach to teaching.

“Jack values your own independence and learning abilities. He will set you up for success because he’s not going to sit there and do everything for you. He’s going to have you do it the first time, and even though he might know that you’re doing something wrong, he’s going to let you figure that out for yourself. I think it’s really valuable that he lets you make mistakes instead of having the pressure of doing everything right the first time,” says Kunze.

Students in the Dino Lab do everything from carefully clearing away the rock around each specimen, to finding fossils in the field themselves. Every summer, Horner brings members of his Dino Lab team on an excavation trip to Montana. They explore the Judith River and Hell’s Creek Formations, large geological regions where countless fossils have been discovered.

This semester in the Dino Lab, Horner and his students are hard at work preparing their latest finds for study. One recent find, a fossil of a prehistoric turtle, has Horner intrigued.

“This is a turtle. It’s about 76 million years old. We found the specimen this summer. It’s not like any other turtle I’ve seen out there, so hopefully it will be an important specimen. With the fossil turtle, the best way to identify it is with the surface texture, and the surface texture on this one is different from most of the turtles that we normally get.”

Professor Horner holds two different fossilized turtle shell pieces. (Photo credit: Mariel Sheets)

The dig team spent several weeks in Montana hiking and digging up fossils like the turtle. They excavated part of a Triceratops skeleton, the rest of which is waiting for them in the ground for when they return next summer. They also found many “micro sites,” which have a concentration of smaller fossils, rather than a large skeleton. Such sites allow Horner and his team to better understand what a region’s ecosystems looked like millions of years ago.

Horner has been digging up dinosaurs in this region for decades, starting with his first discovery at just eight years old, but he prefers to let his students speak about their experiences in the field.

Kunze described her time in Montana as “magical,” and said that she feels a childlike wonder for dinosaurs and discovery.

“Sometimes you can hike eight miles and find absolutely nothing. Sometimes you walk two feet, and you’ve stumbled upon a bone. It just depends on the day. Any bone that I find, I feel like a little kid again instantly. I could be looking at the smallest little pieces in the world, like a digit of a finger. And I will just get so pumped. Like, ‘oh my god, I found something!’ I think it’s so unique that you can find 78-million-year-old bones in the ground. I just get giddy,” says Kunze.

The Dino Lab team also visited the Cretaceous-Paleogene Boundary, also called the K-T Boundary, a layer of the earth’s crust marking the asteroid crash that wiped out the dinosaurs in the geological record.

“You can see the extinction line, and it was mind-boggling. I kind of just had to stand there and look at it like, ‘oh, like, this is the extinction event. We’re standing on it.’ It was a very magical moment,” says Kunze.

Kunze and another member of the dig team stand atop the K-T Boundary Layer. (Photo courtesy of Greta Kunze)

Finn Finney, ’26, another student volunteer at the Dino Lab, says going to Montana helped her find a new passion for paleobotany (the study of prehistoric plants) after Horner put her to work digging up plant fossils.

“I was working in a bog, getting some fossilized plants and leaves and stuff. That was my favorite part of the dig. I sat on the ground using my little rock pick, digging holes. And then I would pick layer upon layer trying to see if any fossils were on either side. I was especially looking for ginkgo leaves because that’s what the dinosaurs had. You could find them fossilized in the ground, and they’re really pretty.”

Finn Finney, ’26, Dino Lab Volunteer, examines some specimens. (Photo credit: Mariel Sheets)

Finney uses a dental pick to clean a fossilized femur found in Montana in 2023. (Photo credit: Mariel Sheets)

Both Finney and Kunze are considering careers in paleontology thanks to their time in the Dino Lab. After working with Horner in the Dino Lab, they describe him as a mentor and a friend who has taken the time to understand their needs and interests.

“I don’t think I have met another professor that also has a reading disorder like I do,” says Finney. “When he told me that, I was like, ‘wait, oh, my gosh, someone just like me!’ It’s a welcoming and understanding environment, because sometimes professors don’t understand that sort of disability. It was very nice to meet a professor who understood.”

Kunze, who is currently authoring a paper on a type of dinosaur bone at Horner’s encouragement, says that “Once you start, paleontology is something you can’t really stop.”

Once the Dino Lab team finishes preparing the bones in their care, the fossils will be studied and displayed at the Burke Museum in Seattle, WA, through the University of Washington. The Dino Lab itself is also on the move, with a new location at the Orange County Discovery Cube in the works.

Horner will return to Montana next summer, on the hunt for ancient bones once again.

The Montana Dig team looking for fossils this past summer. (Photo courtesy of Greta Kunze)