Exploring the Library: The Center for American War Letters Archives

September 20, 2019

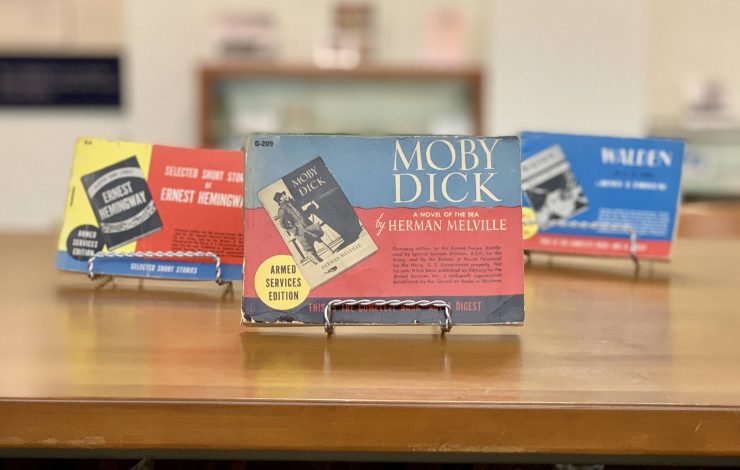

Not only do they house one of the biggest collections of American war letters, second only to the Library of Congress, they also hold other war-related artifacts such as pictures, citations of service, awards, diaries, journals, and Armed Service Editions of books. Before going to the Center for American War Letters Archives, I had never heard of Armed Service Edition books but the concept fascinated me once I discovered what they were. War edition books are novels formatted to be able to fit in a soldier’s pocket or backpack. They’re light and small, making them perfect for a soldier to carry with them. These books range from the classics to history of war books. At the Center for American War Letters Archives, you’re able to get your hands on hundreds of these books. “Back in World War II,” the Center’s director, Andrew Carroll explains, “publishers sent out about 123 million books to troops serving overseas during the war, everything from Hemingway and Fitzgerald to books about science and technology. They were little paperback books called Armed Service Editions.”

Three of the hundreds of Army Service Edition books with in the Center for American War Letters Archives

This incredible feather in the library’s hat is thanks to the Center’s director, Andrew Carroll. Before the Center became the second largest collection of American wartime letters, Carroll received his first war letter in the wake of his family’s house being destroyed in a fire. He received the letter written in 1945 from a relative after hearing about the tragedy. After this letter, he became fascinated with the preservation of war letters. He realized that so many of these letters became lost due to everyday accidents or simply being forgotten. Carroll made it his life’s mission to preserve these artifacts of our nation’s history. In 1998, Carroll launched “The Legacy Project” and recruited the help of the Dear Abby column to begin his endeavor. Due to the extreme media exposure, Americans from all over the country sent Carroll roughly 15,000 letters, thus beginning the vast collection.

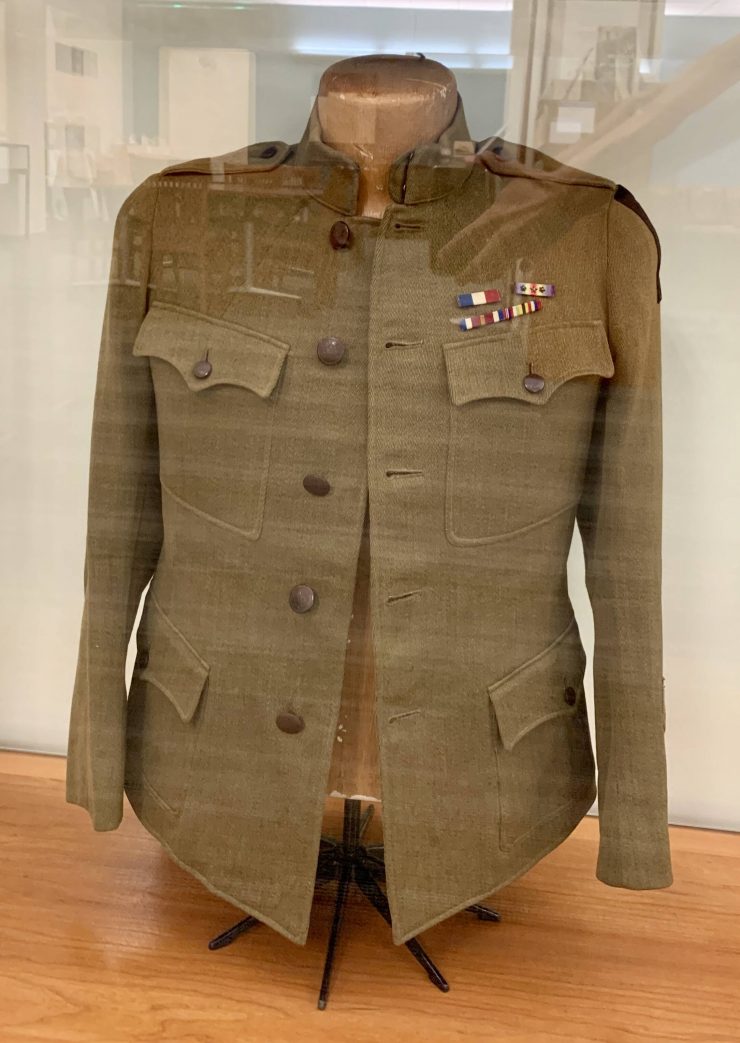

Carroll donated the bulk of his Legacy Project to Chapman University in 2014 and the Project was renamed the Center for American War Letters. Thus, his donation of the Legacy Collection to the Leatherby Libraries began the War Letters Archives. From the beginning, the Center’s mission has been to compile, preserve, protect, and provide access to the letters in the War Letters Archive. With that mission in mind, the Archives has devised a thorough process to prepare their archives to be accessed by the public.

Most letters arrive at the archive via mail by envelopes, packages, and sometimes even in shoe boxes. After they arrive they are accessioned, the act of formally accepting collections into the archive. Each collection is assigned a unique identifying number. Archivists develop a plan for how to process each collection of letters. Processing is the act of physically arranging and describing letters so that researchers and archivists will be able to access them. Many of the letters are also old and fragile so they require very delicate handling and preservation. The letters are arranged into folders, usually organized by author and date. The folders are given a number and title, which describes the contents of the folder. Collections are stored in acid-free boxes, which help protect the letters from environmental damage. The collections are shelved by conflict. The finding aid includes biographical information about the author of the letters. It also describes how the letters are organized so that users may easily access them. It also is used to contain the arrangement and description of the collection, including bio, content, extent of the collection and where to find it. If you ever need to access any letter, the finding aids are uploaded to the Online Archive of California (accessed online at https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/).

When asked how the Center for American War Letters lends a hand in the education of Chapman students, archivist Andy Harman explained: “Students use the war letters to write primary source-based research papers either for historical or political science studies. They use them to understand not only the individual experience of American soldiers during war, but as a window into cultural, historical, and societal norms during a particular time period.

Currently, the Masters program in War and Society has a class called “The Soldier’s War,” in which grad students write a thirty-page paper on a single soldier’s experience of war. They choose a single collection and match it with appropriate secondary sources to argue an original thesis through the lens of a personal experience in the worst of situations.

We also have students and scholars from other institutions all over the country use these collections for similar purposes, and have even had a letter read by a current soldier cadet in a recent documentary on the Holocaust that aired on the Discovery Channel and was sponsored by the USC Shoah Foundation.”

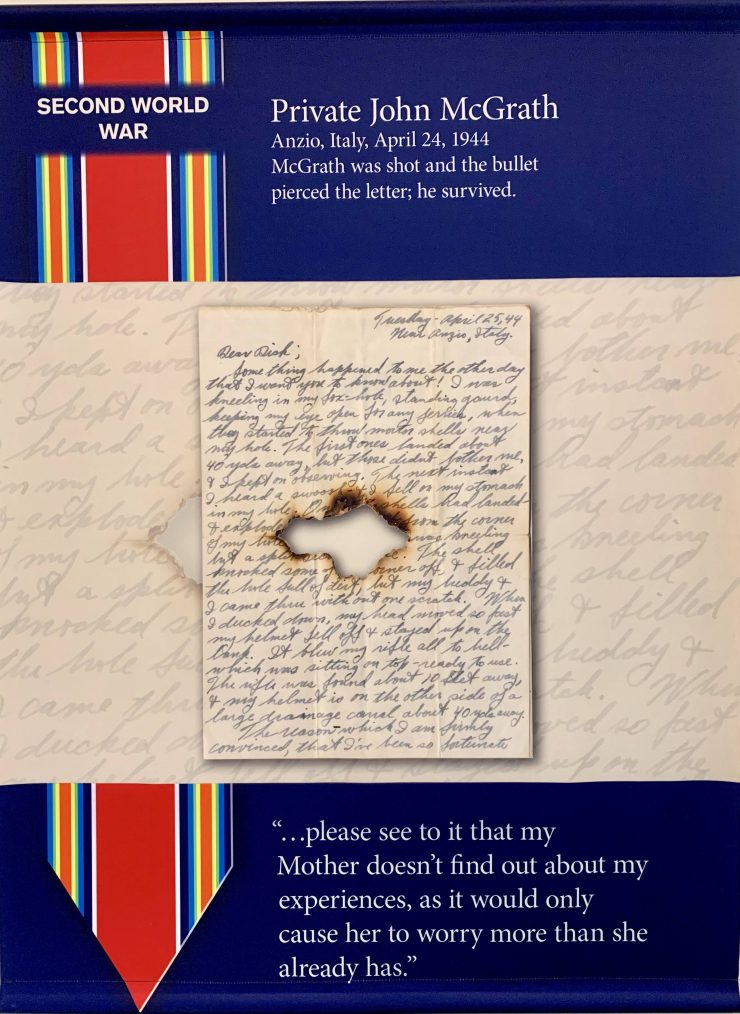

When you enter the Archives, you are greeted by larger than life letters, hung around the room, one from every major war the United States has taken part in. Reading these letters, you realize how different those soldiers’ life experiences were from our own. “Please see to it that my mother doesn’t find out about my experiences,  for it will only cause her to worry more than she already has,” Private John McGrath wrote in a letter during WWII. While carrying this letter, McGrath was shot, piercing a hole through the center of the letter. Surviving the bullet, McGrath was able to send this letter to his family.

for it will only cause her to worry more than she already has,” Private John McGrath wrote in a letter during WWII. While carrying this letter, McGrath was shot, piercing a hole through the center of the letter. Surviving the bullet, McGrath was able to send this letter to his family.

Other letters hung around the room show how the soldiers of the war revealed their honest feelings about the war, such as a letter from the Vietnam War by Warrant Officer John Pohlman. “It matters very little what my views are on the war… The fact is that I’m here, and will be for the next eleven months.” This quote in particular really sticks with me. Pohlman never wanted to be overseas fighting a war, yet, he was forced to. What bothers me even more about this letter is that later that day after writing this, he was killed. This letter shows how unpredictable not just war is, but life itself. He had braced himself to be in Vietnam for eleven more months. Instead, while he was writing that, he was living his last day.

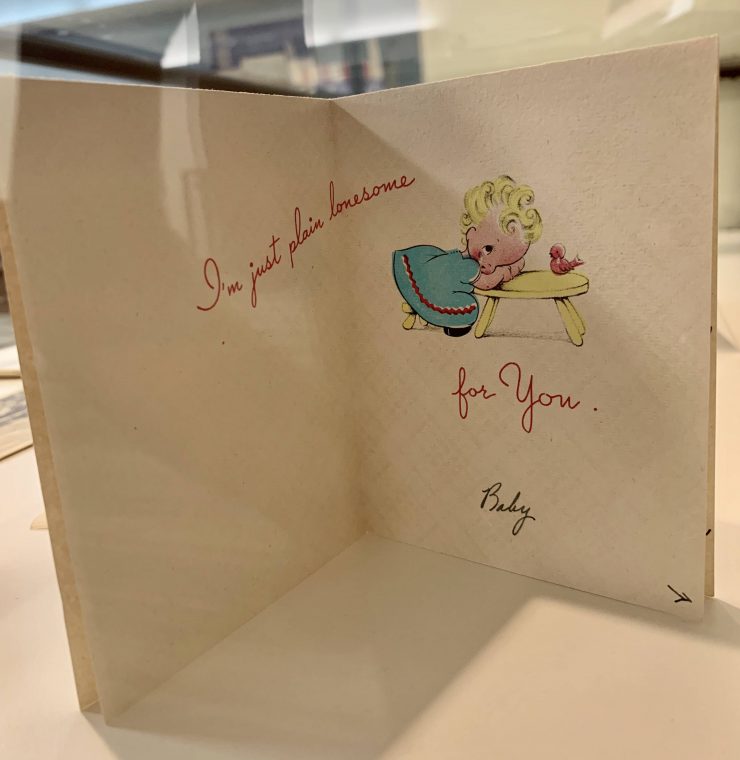

One could spend an entire day in the Center for American War Letters Archives reading about these soldiers’ lives. It’s truly humbling to sift through the vast collection of artifacts the Center possesses. Seeing the longing for home in the words of the soldiers to the love that is shared between letters of loved ones. As Carroll continues to travel the world in search of wartime letters, the archives will only continue to grow. The Center for American War Letters Archives has been and will continue to be one of my favorite places in the library.