Exploring the Library: Russian Icons from the Collection of Evelyn Lalanne

October 11, 2019

This St. Nicholas the Miracle Worker icon contains Old Ritualist symbolism including the two-finger blessing and the IC XC spelling of Christ. Many Old Believer icons were painted over or destroyed after the Great Moscow Council.

“What are icons?” you must be thinking, because if you are anything like me, you have never heard of them before. Thanks to the Leatherby Libraries, I am here to inform you! Icons are paintings of religious figures composed on wooden boards or embossed on metal. Through my research on the topic, I discovered that icons are one of the most recognizable symbols of the Eastern Orthodox faith. Icons act as “windows onto heaven” and offer a direct connection to God. They have adorned walls of churches and houses, as well as necks of believers, for centuries. In the library, we have a large collection of Russian icons, mainly originating from the 19th and 20th centuries.

I work in the fourth floor administrative office. Every day when I come into work, I walk past this collection (located right across from the office so when you visit the Russian Icons display, you can say hello to me). I’ve admired them for their beauty but never really stopped and taken a moment to understand what these Russian Icons were or their history. One thing that I’ve learned about the Leatherby Libraries through these blog posts is that there is so much knowledge within these walls at our disposal; all we have to do is look for it. Once I took a closer look at these artifacts, I was fascinated with the history of Russian Icons.

The first known creation of Russian Icons began around the 10th century in Russia. By the 17th century, icons saturated the Russian landscape. They were hung everywhere, in homes, public places, churches, even hanging from trees on the side of the road. By the mid-19th century, icon production in Kholui, a small Russian village, alone had reached 1.5 to 2 million icons per year and employed all 700 of the town’s residents.

The icon of the Mother of God of The Burning Bush is based on an Old Testament miracle witnessed by Moses. In the Book of Exodus, God calls to Moses from a bush that “was burning, yet it was not consumed” (Ex. 3:2) to say that he will lead the Hebrews from Egypt. The image of the burning bush was then used to symbolize Mary giving birth to Christ while remaining a virgin. These icons were often hung in homes because it was believed that they could protect against fire.

The naturalistic rendering of this Kazan Mother of God icon is evidence of the Western influence on Russian art and culture.

The way icons were viewed by the Russian people really intrigued me. While they are essentially paintings of religious figures, they were not viewed as art. It wasn’t until Western influence was brought into Russia that painting was even considered a form of art. In the eyes of Russia, icons were much more than art, they were a window to God – a window that connects heaven and earth. The main distinction between art and icons was the concept of icons affecting their surrounding environment. After the concept of “art” was introduced to Russia, icons were known as ikonopis which translates to “painting icons.” Ikonopis were in a category of their own, elevated from art as something sacred.

Icons infiltrated every aspect of Russian society. Regardless of economic status, every household had at least one icon. In every house, there would be a “red corner” or “main corner” that would display the household icons. In lower-class houses, the “main corner” would be a simple wooden shelf with the family icons placed on top. Within the houses of the wealthy, the “main corner” would become a sort of domestic church with icons covering the walls.

This small icon was worn as a pendant. It depicts the Three Holy Hierarchs – St. Basil, St. Gregory, and St. John – who were influential bishops of the early church and greatly influenced the development of Christian theology and liturgy.

While icons hung from walls and decorated shelves, they also were worn around the neck. These icons were known as traveling icons. Nearly one-third of Chapman’s collection of Russian icons are small, portable metal icons. The popularity of traveling icons exploded in the late 17th century. These small icons were produced initially by the Old Believers who believed that the Tsarist State and newly established priesthood were figureheads for the Antichrist. Regardless of their rebellious origins, traveling icons became so popular that even the Church began fabricating them. What first started as a rebellion against the new political/religious climate of 17th century Russia, traveling icons eventually became a popular form of religious expression.

Chapman’s collection of Russian Icons were donated by the late Mrs. Evelyn LaLanne in 1990. Mrs. LaLanne was a high school teacher and was passionate about education. She shared her collection with the university with the wish that others might learn from the remarkable images commemorated on these icons. I am confident in saying that Mrs. LaLanne’s donation has educated me in Russian Icons and I hope to share my knowledge with all of you. If I’ve piqued your interest in Russian icons, Chapman University offers a virtual exhibition of all its Russian icons. A virtual exhibition of the icons was created by Jessica Bocinski ‘18 and Dr. Wendy Salmond. The website elaborates on the library’s display and is an easy guide to understanding Russian Icons. Access to this website can be found here: chapmanrussianicons.omeka.net. I had an incredible time reading through the virtual exhibition and I am certain that you will too!

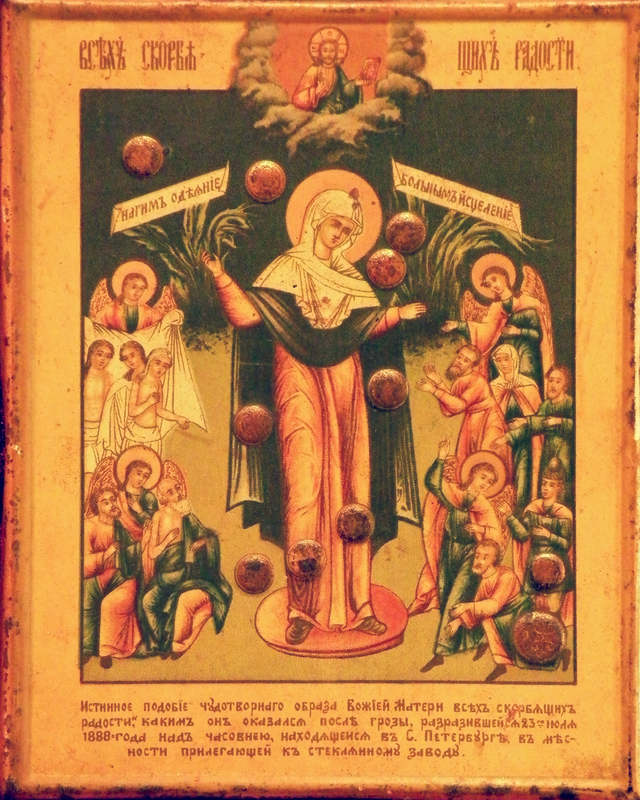

The “Joy to all Who Grieve with Coins” icon became popular in 1888 when a lightning bolt, or “heavenly fire” struck a church in the small village of Klochki, located outside Saint Petersburg. The lightning destroyed the church and burned all the icons within it except this particular icon of Mary. In fact, the soot that had previously darkened the icon was cleared away and twelve half-kopeck coins from the nearby donation jar attached themselves to the icon. News of the icon’s miraculous survival spread throughout the country, and in 1890 the icon was reported as healing a young man named Nikolai Grachev. Many devotional pamphlets attempted to explain the meaning of the twelve pennies. One of the most widely accepted was that Mary used the pennies to associate herself with the poorest classes who used them.