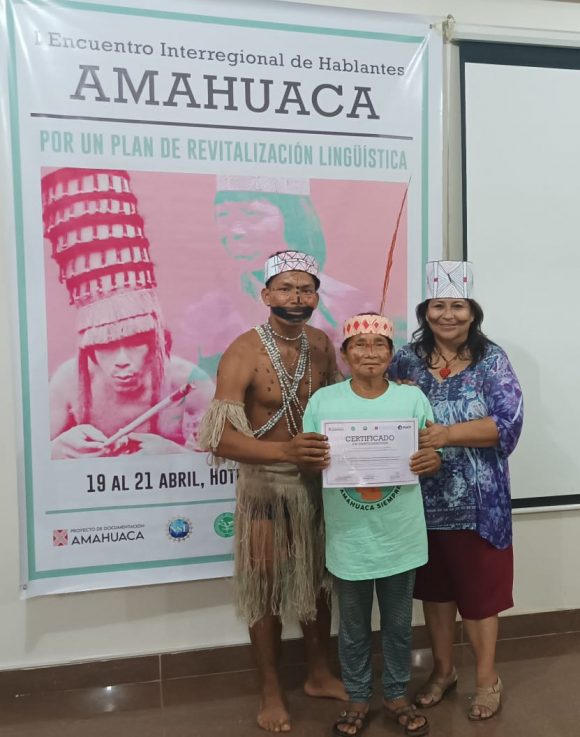

A Historic Event for the Amahuaca People of Peru

May 27, 2023

The Amahuaca people number fewer than 1,000 individuals, of whom only 330 speak the Native language. For the first time, thanks to the work of Wilkinson College’s Dr. Pilar Valenzuela, representatives from all the Amahuaca villages gathered in the city of Pucallpa in Peru to assess the status of their Native language and prepare a two-year language revitalization plan.

Dr. Valenzuela (World Languages and Cultures), co-organized the event, made possible thanks to support from Wilkinson College and grant funding from the National Science Foundation. Dr. Valenzuela and a team of linguists have been studying and documenting the endangered language for the last four years.

The recent meeting in April represents a milestone for the Amahuaca people. This was the first time they were able to meet and discuss common strategies to counteract the ongoing process of language loss.

“One of the many interesting facts about the Amahuaca people is that there are still groups that live in the forest, in “voluntary isolation”, as well as groups that maintain little contact with Peruvian society,” said Dr. Valenzuela. “To my surprise, members of these groups also attended the event!”

The participants created an organization called “Unión Interregional de la Nación Amahuaca (UINA)”, in which Dr. Valenzuela was elected as the organization’s advisor.

One immediate task is to help UINA in becoming an officially recognized organization in Peru. Dr. Valenzuela is currently collaborating with several members remotely to draft the organization’s objectives and regulations, however, there is so much more she has on the agenda.

“My main goal is to support the Amahuaca groups in accomplishing their language revitalization objectives. Take, for example, those residing in Boca Pariamanu, a village in the Madre de Dios region where the language is no longer spoken. They’re actively raising funds to bring a fluent Amahuaca speaker from the Ucayali region to teach them the language. My support will consist of providing training in second language teaching methods and in the use of pedagogical materials prepared by our project, including a trilingual (Amahuaca-Spanish-English) dictionary, a dedicated book for facilitating reading and writing in Amahuaca, and a bilingual story book,” explained Dr. Valenzuela.

UINA took the initiative to create a WhatsApp group, enabling effective communication among members who have (sporadic) internet access. It is remarkable that people who had no clue about each other just a month ago are now engaging in chat discussions, sharing news, posing questions, and expressing their opinions about the organization, their culture, and their future.

Dr. Valenzuela wants to improve language materials as well as create new ones so they can be used in Amahuaca elementary schools, where currently these schools do not have an Amahuaca teacher, and the language is not being used at all. She hopes to work with the Regional Secretary of Education of Ucayali and with the few Amahuaca people who have a high school diploma, so that they become elementary school teachers in the Amahuaca villages.

Finally, she wants to help obtain grants for the Amahuaca people to support language revitalization activities and the development of an educational model rooted in community cultural practices, values, and aspirations. For the groups in “initial contact,” there is the urgent need to have a school where they can learn reading, writing, as well as basic arithmetic. However, “it is crucial that this school be community-oriented, integrate Amahuaca knowledge and language, and have a flexible schedule organized around the community calendar. This will enable the Amahuaca to maintain their unique identity while gaining the essential knowledge and skills required to engage with Peruvian society on their own terms, minimizing the risks of exploitation and marginalization,” said Dr. Valenzuela.

“It is such an amazing, exciting opportunity to work with the Amahuaca people, including those who live in the Amazon rainforest practically self-sufficiently. Having the privilege to connect with this community motivates me to spread awareness, both within Chapman and far beyond. The potential for mutual learning, exchange, and collaboration with the Amahuaca people is immense. They have so much knowledge and unique experiences to offer, which can enrich our perspectives and inspire meaningful partnerships.”

Below is a video with clips of the event that happened in April 2023.

- Gino Machay Sarasara (first speaker video): A young man who is the only Amahuaca attending a university. He talks about the importance of the event because the Amahuaca people, culture, and language are in danger of extinction.

- Elisbeth Andrades Picon & Antonio Rodriguez (second and third speakers in video): They come from different areas. They talk about how happy they are for having the chance to participate in the event and get to meet their “relatives” for the first time. The woman mentions the importance of passing on the language to children.

- Genis Cardenas Flores (fourth speaker in video): A man from the Reserva Indígena Murunahua. He is saying they want access to school to learn how to read and write, and also access to medical care.

The Murunahua Indigenous Reserve is a protected area in Peru for indigenous peoples in situations of isolation and initial contact. It has an area of 470,305. It is located in the districts of Yurúa and Antonio Raymondi, province of Atalaya in Ucayali. The objective of the reserve is to protect the rights, habitat and conditions of the isolated indigenous peoples Murunahua, Chitonahua and Mashco Piro and the indigenous people in initial contact Amahuaca. It was created as a Territorial Reserve in 1995. In 2016 it became an indigenous reserve.