Visual Culture Expert Stephanie Takaragawa Awarded a $100,000 California Civil Liberties Grant

September 19, 2023

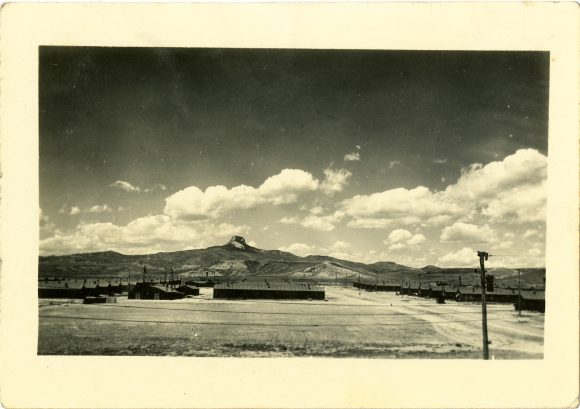

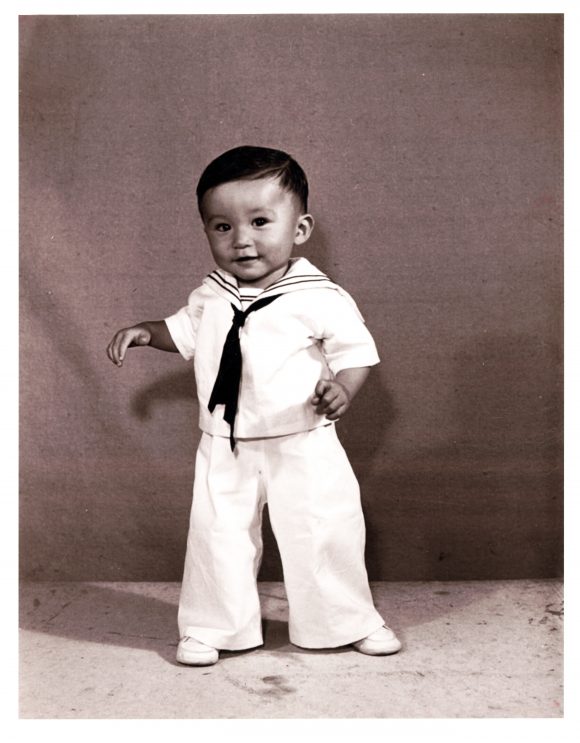

When Miyoko Takaragawa (1922-2015) died, her family found two photo albums among her possessions that included over 100 photographs taken at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, a World War II Japanese American confinement site. Miyoko and her husband, Yutaka Takaragawa, were incarcerated at Heart Mountain from 1942 to 1945, where their son Tetsuro Ronald Takaragawa was born. Miyoko’s mother, Koyoshi Shitamoto, ran a popular sewing school at Heart Mountain and, after her release from the camps, decided to move the family to Colorado to start a new sewing school. Unfortunately, none of the surviving family members know who took the photos or who many of the subjects were.

When Miyoko Takaragawa (1922-2015) died, her family found two photo albums among her possessions that included over 100 photographs taken at Heart Mountain Relocation Center, a World War II Japanese American confinement site. Miyoko and her husband, Yutaka Takaragawa, were incarcerated at Heart Mountain from 1942 to 1945, where their son Tetsuro Ronald Takaragawa was born. Miyoko’s mother, Koyoshi Shitamoto, ran a popular sewing school at Heart Mountain and, after her release from the camps, decided to move the family to Colorado to start a new sewing school. Unfortunately, none of the surviving family members know who took the photos or who many of the subjects were.

These photos are precious documents of a history seldom studied or discussed at length, although a significant chapter in United States history. With the support of a $100,000 grant from the California State Library California Civil Liberties Public Education Program, Miyoko and Yutaka’s granddaughter, Dr. Stephanie Takaragawa (Sociology), hopes to identify the people in the images and put together an essay about the life of the Takaragawa family at Heart Mountain and what happened to them after they left the War Relocation Center.

These photos are precious documents of a history seldom studied or discussed at length, although a significant chapter in United States history. With the support of a $100,000 grant from the California State Library California Civil Liberties Public Education Program, Miyoko and Yutaka’s granddaughter, Dr. Stephanie Takaragawa (Sociology), hopes to identify the people in the images and put together an essay about the life of the Takaragawa family at Heart Mountain and what happened to them after they left the War Relocation Center.

The Takaragawa family collection of photographs will help us understand what life in the incarceration camps looked like and how incarcerees chose to remember their experiences.

“I have bits and pieces of my family history that I’ve collected from family, but no one really has the whole picture. My grandparents NEVER spoke about it. This grant will provide me the time and resources to put my family history together and get a better sense of what their lives were like before, during, and directly after incarceration. I’m grateful for this opportunity, but also think it’s so important for so many members of my family, and other families who have shared a similar hidden history.” – Dr. Stephanie Takaragawa

Once the research is complete, Takaragawa will use the family photographs to create an online photo essay of the family’s life inside camp and their journey back to California. Using the online photo essay as a digital storytelling model, detailed pedagog ical materials will offer advice on creating a family history photo essay for middle, high, and college teachers and students who will learn how to tell their own digital stories through photographs. The project team, which includes Dr. Jan Osborn (English) and Jessica Bocinski (Manager of The Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art), will also develop podcasts and instructional YouTube videos. In Spring 2024, the project team will deliver classroom presentations in California schools and community workshops on incarceration topics to assist in bringing this content to the classroom and community.

ical materials will offer advice on creating a family history photo essay for middle, high, and college teachers and students who will learn how to tell their own digital stories through photographs. The project team, which includes Dr. Jan Osborn (English) and Jessica Bocinski (Manager of The Phyllis and Ross Escalette Permanent Collection of Art), will also develop podcasts and instructional YouTube videos. In Spring 2024, the project team will deliver classroom presentations in California schools and community workshops on incarceration topics to assist in bringing this content to the classroom and community.

While photography was highly restricted in incarceration camps, today, cameras are ubiquitous as part of standard smartphones. While the internet has become an increasingly accessible and inexpensive vehicle to share photographs, the intentionality of the value of a photographic image has changed. In some ways, the omnipresence of photographs has made us less, not more, thoughtful and intentional about their use. This is an excellent moment to retrain youth to use photographs intentionally, not simply for “selfies” or “likes.” They already have this tool, so this project, “Through Internees Eyes: Japanese American Incarceration Before and After,” seeks to help them connect photography with their own family stories.