Black Beauties: More than just pretty girls Dr. Charissa Threat rediscovers the forgotten black female pin-ups of WWII

February 21, 2020

While searching through the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) archives, history professor Dr. Charissa Threat came across something peculiar. It was a letter written by two black soldiers in WWII sent to the NAACP asking for pin-up images of black women.

“We don’t have enough images of black women,” said Threat paraphrasing the soldiers’ letter.

Dr. Charissa Threat

Pin-up images, images of glamorized women starlets and models, reached the height of their popularity during WWII, serving as distractions and morale boosters for soldiers to literally “pin-up” during the war. However, most of these models were white.

“I was struck by the fact that these two black soldiers would write to this organization that was rather conservative at that moment in time, during WWII, and was focused on [combating legal] discrimination,” said Threat.

The NAACP wrote back, unable to take action, and redirected the men’s request to local news outlets.

“I thought the letter was curious and held on to it,” said Threat.

Ellen Stewart, “Pin-up Girl,” Chicago Defender, 7 April 1945, pg. 15

Shortly after finishing her first book, Nursing Civil Rights, Dr. Threat revisited that letter she held on to, wondering what had happened. Threat found that the NAACP had forwarded the request to the Pittsburgh Courier, a major nationally-distributed black newspaper. Upon further investigation, she saw similar appeals in the Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro-American from other soldiers. Columnists and soldiers were writing to women in African American communities, asking them to send their portraits. And they did.

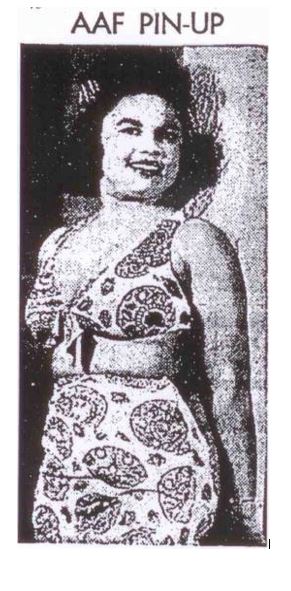

Eleanor Morris, “AAF Pin-up,” Chicago Defender, 26 May 1945, pg. 14

“What people know about the pin-up’s narrative is very one-sided. The images that we hear about are African American entertainers like Lena Horne. But we really don’t hear about regular African American women doing this,” Threat explained. “I like to not only challenge traditional narratives, but also help people to understand that the narratives of black women in WWII are much more than they tend to know especially because what we do know about African American history is so small.”

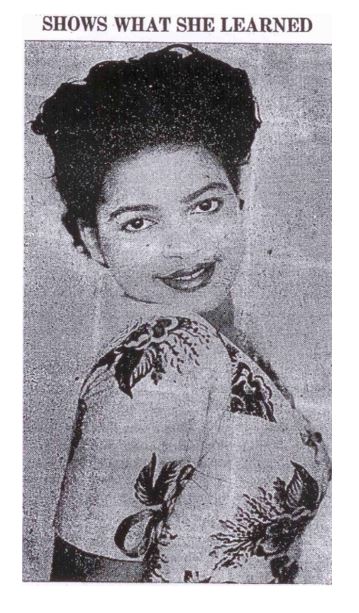

Like some of their white counterparts, black female pin-up pictures depicted more than physical beauty. Soldiers were really interested in images of the girl who had it all—who was well-liked in her community, had an education, was a member of a church, and had a great job. This phenomenon grew as black army units would even select a favorite pin-up girl to be published in stateside newspapers as their favorite “camp sweetheart.”

“Shows What She Learned,” Chicago Defender, 24 March 1945, pg.11.

For Threat, this story is about more than just pictures of “pretty girls.” “For these black soldiers, they were really thinking about maintaining community relations back home,” said Threat. These pictures gave something for black soldiers to rally behind: preserving their home, their people, and the future of their communities.

Threat has received several awards for her work on black pin-ups, including a Mellon Faculty and Residence Fellowship and a highly-coveted National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. She intends to expand this initial research into an article and book exploring black emotional intimacy during WWII.