From Our Eyes: The Warped Side of Our Universe

February 28, 2024

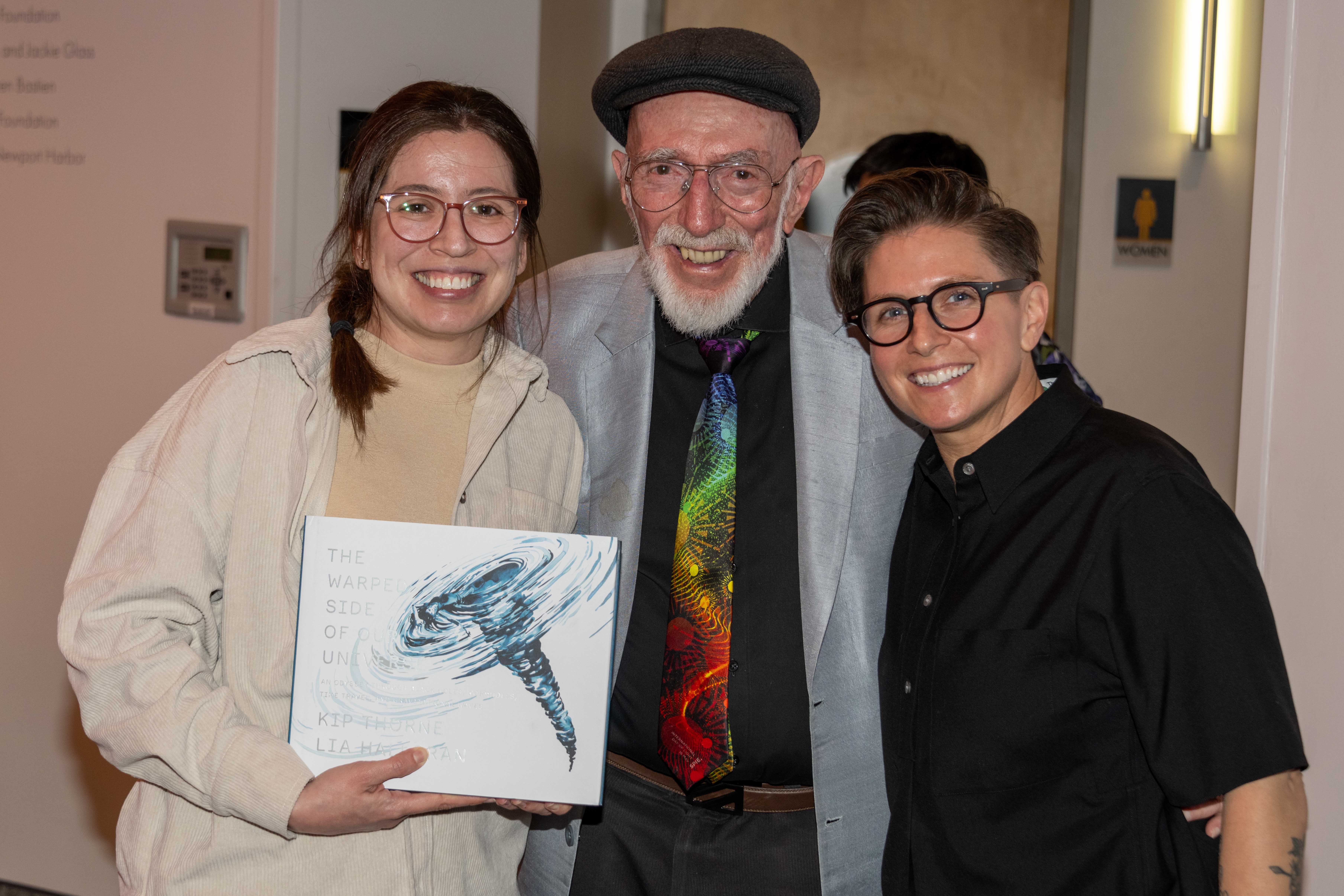

(Left to Right) Event attendee, Kip Thorne, Lia Halloran Photo courtesy of Chapman Special Events.

This edition of From Our Eyes features Lisa Wong, (‘25, Broadcast Journalism and Documentary major and double minor in Chinese and Visual Journalism). Wong attended The Warped Side of Our Universe event which featured President Daniele Struppa moderating a conversation with Nobel Laureate in Physics Kip Thorne and Associate Professor of Art, Lia Halloran on their book, The Warped Side of Our Universe.

I never understood science.

It’s safe to say that most people quickly understood what school subjects they excelled at and were excited about, and which ones they weren’t. For me, that was math and science.

That’s basically my attitude towards anything science related. Wormholes? Quantum physics? Gravitational waves? Sure, that’s all interesting. I love learning about the universe and the space beyond what we know. But oftentimes, accessing that knowledge feels impossible. The language of the universe feels intangible to the parts of me that gravitates more to storytelling, creativity, and art.

On February 19, 2024 in the Folino Theater, Nobel Laureate Kip Thorne and Chapman University Associate Professor of Art Lia Halloran discussed the release of their book The Warped Side of Our Universe, and unveiled the decades-long process of its production.

The book follows a space traveler who travels through wormholes and black holes, which presents a vulnerable experience of what we know and don’t know about the universe. Thorne’s poetic writing explores this narrative. Accompanied by Halloran’s paintings, together they create a tangible project that meshes the technicalities of science in a visual medium.

In a discussion facilitated by Chapman President Daniele Struppa, Thorne and Halloran explored the intersection of art and science, and how that connection can bridge the gap people like me feel with learning about concepts such as time warps and black holes.

As the three talked, pieces and animations from Halloran’s paintings played on the screen – taking the audience through swirls of deep and light blues that represent the eloquence and mystery that is our universe.

“[Blue] simultaneously represents depth and darkness of the universe, but it also has luminosity,” Halloran said. “I thought it was a nice, sort of poetic parallel to Kip’s writing,” she said.

The book is compiled of 300 original paintings from Halloran which details the scientific discoveries astrophysicists, including Thorne, have unraveled with LIGO – an observatory designed to detect cosmic gravitational waves.

Halloran first learned of Thorne back when she was a graduate student in Yale, studying art and taking astronomy courses. She had read Thorne’s Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein’s Outrageous Legacy, which she said ‘transformed the experience of what science could be.’ “I felt like I was invited to be a part of something bigger,” she said.

Kip Thorne, Lia Halloran and Chapman President Daniele C. Struppa on stage at The Warped Side of Our Universe event. Photo courtesy of Chapman Special Events

Five years later, Halloran met Thorne at a party, where she began gushing about how much his work influenced her studies in school. Impressed, Thorne visited her studio and got to know Halloran. He even used her sketches to show Steven Spielberg, who was the original director of the soon to be groundbreaking and Academy Award winning movie, Interstellar. Thorne would continue as an executive producer and scientific advisor for the film, which was eventually taken on by director Christopher Nolan.

Those interactions were just the start of Thorne and Halloran’s collaboration, leading to the creation of The Warped Side of Our Universe. The production of the book also featured support, research, and assistance from some of Halloran’s art students. In quite a full circle moment, just as Halloran reached out to Thorne about collaborating, these students did the same with her.

Furthering the progress of science, art, and making science more accessible are values that Thorne and Halloran shared they want to make possible through this project. They hope that more projects like this will come about in the future.

“Science can inform art in the way that we challenge and try to understand the natural world around us. And art can help us in the other way, [to] actually describe and come up with ways that you can see from a different angle,” Halloran said.

“Art is a tremendously powerful tool for communicating science and for embodying [it] in a visual and visceral way,” Thorne said. “Because these visualizations are central to synthesizing to really understand in an intuitive way what is going on in the universe,” he said.

There’s not just one way to look at science. The avenues to understanding the nature of the universe goes beyond just a mathematical lens. There are various artistic and technical paths, and there’s an intersectionality between these paths to provide an even greater unveiling of what we know and don’t know yet.

The book talk and discussion wrapped up with a Q&A portion, where the question that I submitted was asked: “After diving into all this research into [the universe], what other questions do you still have that are unanswered?” They answered that they want to focus on the Big Bang and how the laws of quantum gravity play into the birth of the universe, “which Thorne’s LIGO could help give answers to,” Halloran said. Thorne predicts these discoveries are coming in the next few decades.

If more collaborations from students, professors, and people from different fields continue to come together like Thorne and Halloran have, we may be able to find those answers even sooner!