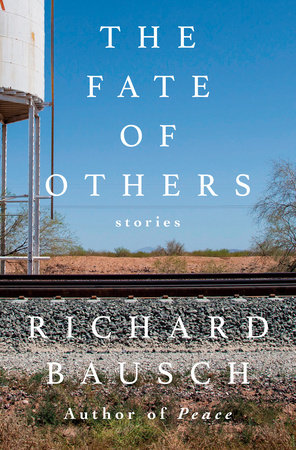

Faculty Books: The Fate of Others

April 14, 2025

In The Fate of Others: Stories (Knopf, May 2025), award-winning author Richard Bausch (English) shares a new collection of short stories that explore the layers of ordinary characters and the subtle complexities of betrayal, grief, and solitude that define the human experience.

This is Bausch’s 10th book of short stories, but this is his first collection where all the stories were also published in magazines.

A fact he is proud of.

“In my other nine books of stories I’ve published, there’s often been a novella that magazines considered too long. So, this is the first collection where every one of the twelve stories can be found in a magazine publication,” he said.

The first novella, called “Donnaiolo,” is 49 pages long and was published in Narrative Magazine, and the second one, “Broken House,” which occupies the last 96 pages of this collection, was originally published in New Letters Magazine.

The Voice of Wilkinson sat down with the author to discuss The Fate of Others: Stories.

Voice of Wilkinson: Your 10th book of stories. What an accomplishment. I understand you started writing the story “Broken House” a long time ago. Tell us about that.

Richard Bausch: I began “Broken House” when I was at the Iowa Writers Workshop 50 years ago in Iowa City, Iowa. I called it “The Most Terrible of Private Crimes.” It was based on the experience of being with a group of altar boys at a monastery, where the monk hosting us said, “There’s an old, old house down that way in the woods. You all can go down there and tear that apart if you want to.” The one line from that early attempt that survives, other than what the monk told us, is “Irony is lost on the young.” In the final version, it reads, “Irony, as we all know, is lost on the young.” What follows in this final version is what we did—we tore that old place apart. That is described in as exact detail as I could muster from memory, except that the context is all fabricated. There was nothing in the early apprentice work, as I think of it, but the tearing down of the house and the discovery that the monk had been speaking figuratively. Nothing about the larger picture, and nothing giving forth the metaphor that the ‘broken house’ is actually the Church, as it so grievously was and has been.

Richard Bausch: I began “Broken House” when I was at the Iowa Writers Workshop 50 years ago in Iowa City, Iowa. I called it “The Most Terrible of Private Crimes.” It was based on the experience of being with a group of altar boys at a monastery, where the monk hosting us said, “There’s an old, old house down that way in the woods. You all can go down there and tear that apart if you want to.” The one line from that early attempt that survives, other than what the monk told us, is “Irony is lost on the young.” In the final version, it reads, “Irony, as we all know, is lost on the young.” What follows in this final version is what we did—we tore that old place apart. That is described in as exact detail as I could muster from memory, except that the context is all fabricated. There was nothing in the early apprentice work, as I think of it, but the tearing down of the house and the discovery that the monk had been speaking figuratively. Nothing about the larger picture, and nothing giving forth the metaphor that the ‘broken house’ is actually the Church, as it so grievously was and has been.

VoW: Let’s talk about your writing process.

RB: I try to work every day on whatever is underway, sometimes breaking off one thing to mess with another. “Broken House” I picked up again, after all the years, in the winter of 2022 and worked through the spring on it. Maybe even into the summer. The story “Isolation” was written during the COVID-19 plague, and arose out of my thinking about Katherine Anne Porter’s great plague story (written during the so-called Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918), called “Pale Horse, Pale Rider.” The whole start of Porter’s piece was actually casual—like a kind of daydreaming, at the level of ‘this is a plague,’ and I wonder if I could write something about it, as Ms. Porter did.

VoW: Do you have a favorite story in this collection?

RB: I honestly don’t really have a favorite. The two most recently written ones, “A Local Habitation and a Name” and “The Long Consequence” (both published in Narrative Magazine), are the freshest for me. One thing I’m very proud of is that the former is from the point of view of a woman, as is “The Widow’s Tale” (and it dawns on me that in both of those, the woman is a widow—except that in ‘habitation’ the dead spouse is also a woman), and that the latter is from a sort of hybrid omniscient point of view.

VoW: Tell us more about “Local Habitation and a Name.”

RB: In that story, I’m writing from the point of view of a woman who, with her female partner, as soon as the Supreme Court Ruling came down in Obergefell v. Hodges legalizing same-sex marriage, acted within the new law at the cost of the female partner’s relationship with her devoutly Catholic, widowed father. The COVID-19 pandemic hits, and the two women have to move in with the old man. They manage the awkwardness of their differing beliefs, and then the old man’s daughter is slain in a mass shooting. So it’s now just the ‘daughter-in-law’ and the old man, both in deep grief over the loss of the spouse/daughter. That story’s first scene, as I began it, takes place on the first morning after the death of the spouse, my protagonist waking in the old man’s house, hearing him coughing in the kitchen, and she’s in the dead woman’s childhood bedroom. But then, after a couple of days’ worth of work, I realized I had to go back. So, I began with a flashback and was well into that before I could see that it should be the story’s opening passage. And I didn’t know until the very last line, how it would end.

VoW: What do you hope readers will gain from reading these short stories?

RB: I’d hope to engender in readers the kind of feeling I myself get when I read any good story, the same sort of ‘opening out’ followed by the attendant journey ‘in.’ That is the sort of recognition about the life we are speeding through, as Saul Bellow puts it, that makes for the sense, however fleeting, that one is not so much alone. That, in fact, at least while the story is being read, one is actually accompanied and companioned in the way that Art, if it’s any good, always makes us feel.

VoW: What are you currently working on now?

RB: My new novel, of which I have 154 or so pages, is called Chopin’s Ghost: A Fable. I’m hoping to finish it before the summer is over. Hoping. I’m also working on a couple of new stories: one called “Murfreesboro,” and the other is a very new and strange one called “Here We Are in Happier Times.”

VoW: Good luck. We look forward to reading them!