Diving Deep Into the Letters of Laura Riding and Gertrude Stein Faculty Books

July 10, 2023

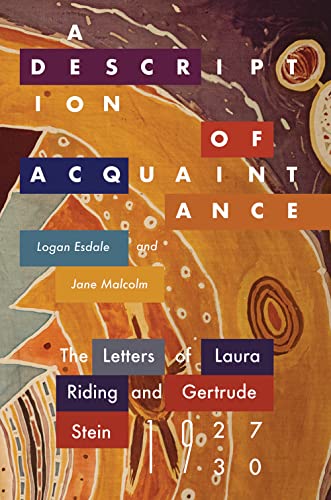

A new book by Dr. Logan Esdale (English) and co-editor Jane Malcolm follows American poets Laura Riding and Gertrude Stein’s captivating, but brief, friendship and marks the first time their personal letters, as a whole, have been made available to the public.

A new book by Dr. Logan Esdale (English) and co-editor Jane Malcolm follows American poets Laura Riding and Gertrude Stein’s captivating, but brief, friendship and marks the first time their personal letters, as a whole, have been made available to the public.

The Voice of Wilkinson spoke with Dr. Esdale about A Description of Acquaintance: The Letters of Laura Riding and Gertrude Stein, 1927-1930, available from University of New Mexico Press. He was delighted to share what he hopes readers will gain from learning about these two seminal writers of turn of the century American poetry and literature.

Voice of Wilkinson: Tell me a little about the book and why you wrote it.

Logan Esdale: A Description of Acquaintance collects the letters exchanged between Gertrude Stein and Laura Riding. Both were Jewish American women who moved abroad, Stein to Paris in 1903 and Riding to London in 1926. They went there to establish themselves as writers and to find certain personal freedoms not readily available in the US. In 1927, Riding published a perceptive essay on Stein’s writing and then, having started Seizin Press with Robert Graves, she approached Stein and invited her to submit a book-length text for publication. This invitation prompted Stein to send a long prose poem and initiated a correspondence between the two women that lasted until 1930.

A Description of Acquaintance includes an introduction, the letters and their annotations, and a selection of relevant contextual materials. The introduction and annotations set the scene and fill things in, while the three-year correspondence offers readers two primary narratives to follow. First, we see the community building that Modernists did through small-press publishing. Riding and Stein, publisher and author, collaborated on the making of Stein’s book, An Acquaintance with Description, which came out in 1929; in this literary world, writers depended on mutual support. Modernists like Stein have since been canonized, but at the time they were marginal figures who relied on other artists for publishing opportunities and recognition. Second, we see a relationship that starts impersonally, even transactionally, but becomes intensely personal. By 1929, Riding looked to her correspondent as someone who understood her, someone to lean on and love. It was therefore bewildering and deeply upsetting when, in 1930, Stein stopped responding, shattering the intellectual and affective bonds that had been created.

When I read the letters in university archives, some years ago, I immediately felt that—with their distinct beginning, middle, and end—they comprised something like an epistolary novel of the 18th century. I thought there was a good chance that even readers not familiar with the Modernists would find these letters interesting. And there has been the perception that Stein was closer to fellow male artists than female; indeed, most letter collections involving Stein thus far have had a man as her correspondent. A Description of Acquaintance contributes to our understanding of the role that women played in Stein’s life and career.

VoW: What do you hope readers will gain from reading your book?

A Description of Acquaintance will appeal, first, to scholars of American literature and Modernism as the book is a contribution to literary history. It has the apparatus of an academic book—an introduction, endnotes, annotations, and an index. These features clarify the social and intellectual context of the late 1920s and allow us to track and understand the role that, for instance, transition magazine or the artist Len Lye played in connecting Stein and Riding. The book documents a crucial period for both writers. Riding was writing many of her most important poems, collected in, for example, Poems: A Joking Word (1930), and in late 1929, after barely surviving a suicidal jump from a window, she moved to Mallorca and, with Robert Graves, established an artist’s colony. Stein was working on How to Write (1931) and, inspired by Seizin Press, she and her partner Alice Toklas started their own publishing venture, Plain Edition. Graves’s autobiography Good-bye to All That (1929), which features prominently in the letters, would be a model for Stein’s bestseller The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas (1933).

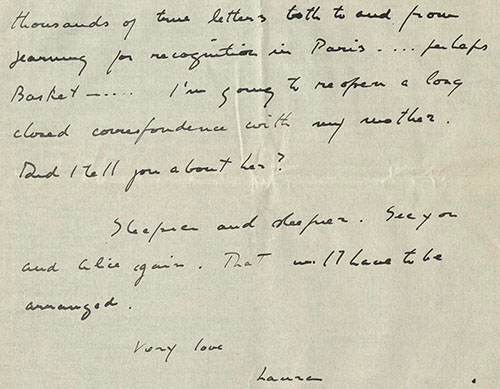

I hope that readers enjoy the letters themselves and the insight they offer on how people in the 1920s corresponded. We transcribed the letters so that they resemble the manuscripts, with spelling idiosyncrasies and irregular spacing intact. Besides the typical letter—stationery in an envelope—they sent telegrams and postcards (some of which are reproduced in the book). They also sent many objects with the letters: textiles, books, found language, poems, drawings, a newspaper clipping, even pebbles. The page design and all of this supplementary information should make the material reality feel accessible to readers. And because letters, no matter how introduced or annotated, are fragments of a larger dynamic, I encourage reading imaginatively. The stories we get are in pieces and we can put them together in more than one way. This is not the smooth narrative one gets in a biography; this has gaps that we may not be able to bridge and references that can lead us in various directions. In the end, I predict that readers will consider the reasons why Stein ghosted Riding. Why did Stein stop replying? Do we need closure?