Design for Emergency Management Faculty Books

September 11, 2023

Do you know how to handle an emergency? Few do. Tunnel vision occurs at all levels—emergency managers, first responders, tourists, commuters, community leaders, and local residents. This is why Professor Claudine Jaenichen (Graphic Design) and a team of professionals from The Design Network for Emergency Management (DNEM) created Design for Emergency Management.

Do you know how to handle an emergency? Few do. Tunnel vision occurs at all levels—emergency managers, first responders, tourists, commuters, community leaders, and local residents. This is why Professor Claudine Jaenichen (Graphic Design) and a team of professionals from The Design Network for Emergency Management (DNEM) created Design for Emergency Management.

The book combines theory, practice, and a range of interdisciplinary case studies to underscore the critical relationship between design and emergency behavior/response in communities.

Design for Emergency Management invites readers from design, humanities and social sciences, science, disaster psychology, emergency management, and the public to participate in building resilient communities through effective emergency preparedness and communication. The book’s message is especially important, given the recent disaster we all witnessed of the beautiful town of Lahaina in Maui being ravaged by wildfires in early August 2023.

The Voice of Wilkinson sat down with Professor Jaenichen to discuss her latest publication.

Voice of Wilkinson: How was the idea of this book created?

Professor Claudine Jaenichen: DNEM was started in 2016 with five interdisciplinary designers from different continents (New Zealand, Taiwan, USA, South America, and Europe) who shared creative and academic scholarly work in emergency preparedness and response. DNEM’s primary mission is to advocate for public understanding and accessible information before, during, and after emergencies through evidence-based design best practices.

We wanted to ensure the book presented the latest, most relevant, collaborative, and interdisciplinary research on how design and design thinking contribute to increasing disaster and risk literacy. Chapters highlight applied research and implementation before, during, and after emergencies, resulting in design guidelines derived from best practices.

VoW: Tell me a little about the book.

CJ: This book fuses interdisciplinary design approaches that are holistic, accessible, and inclusive. Where emergency management is risk-driven and primarily based on quantitative data, design is motivated by empathy, focused on an individual experience, and underpinned by qualitative data. In this book, we showcase many case studies that highlight the added value of design when applied to emergency management and the synergies that occur when these disciplines align with a mutual goal.

VoW: It is mentioned that the book provides new ways of looking at challenges, can you talk about that?

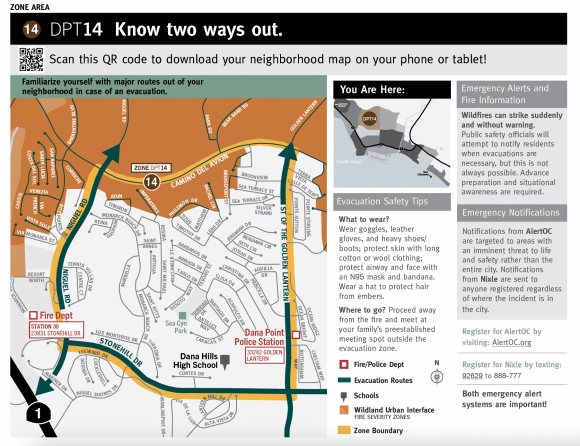

Dana Point public-facing wildfire risk literacy map created by The Design Network for Emergency Management .

CJ: I have worked with California cities to create public-facing wildfire risk literacy maps right after the Camp Fire in 2018. Emergency management used (and still uses) maps intended for trained personnel that are highly dense with data-coded information and repurposes them as public-facing information. These maps needed to provide the appropriate level of information that was understandable.

Applying research in disaster cognition, reduction design patterns, persona development, and information design principles, I developed visual grammar and revised the maps into a diagrammatic infrastructure intended for the public. Prioritizing branding principles of repetition and consistency in the distribution of information was also a new way of repositioning risk literacy as a brand in itself.

VoW: Your referencing of the 2018 Camp Fire makes me think of the recent Lahaina fire. How might the lessons and research in Design for Emergency Management have helped.

Reflecting on the Lahaina fire, communication blackouts had a devastating role in how events deteriorated. Residents have said that there was no organized evacuation and that they had never been trained on how to leave town in the event of a fast-moving wildfire. The decision not to activate the warning siren gained a lot of attention in the days that followed. Thinking of my work in public disaster cognitive phenomena (e.g., tunnel vision, temporary cognitive paralysis, crowd behavior, etc.), I agree with that decision.

Public training with sirens in Hawaii and, most of all, coastal cities on the West Coast have been repeatedly and directly associated with tsunamis. The State of Hawaii Emergency Management Agency lists warning sirens for all hazards on its website but does not include them under the “wildfire” section.

Public training with sirens in Hawaii and, most of all, coastal cities on the West Coast have been repeatedly and directly associated with tsunamis. The State of Hawaii Emergency Management Agency lists warning sirens for all hazards on its website but does not include them under the “wildfire” section.

The Emergency Management website for Maui County does not have a wildfire section at all, so the use of warning sirens is absent as part of responding to wildfires. The State of Hawaii includes warning sirens for all-hazard but does not include the different meanings the siren implies for various disasters. For example, the warning siren used for a tsunami has directional meaning—move up and inland. If the siren was used for the Lahaina wildfire, with no visibility on the ground and no previous practice, mention, or application in a wildfire, the meaning of a warning siren could trigger the trained response to move uphill or inland.

Voice of Wilkinson: What do you hope people will learn from this book?

CJ: The field of design and design thinking includes mechanisms to identify and assess the effectiveness of systems. The book exemplifies design research and projects from different continents as we experience the international effects of climate change. We hope in doing so, we continue to provide and explore examples and opportunities to improve how information is learned, understood, and remembered before, during, and after a disaster through community risk literacy and information transparency.