Faculty Books: Documenting the World A Q&A with Professor Tom Zoellner

May 22, 2020

The dream of being a journalist came true for Professor Tom Zoellner (English), who wrote for a succession of daily newspapers across the country before coming to Chapman University.

“It was a terrific career for about ten years until the Internet took its toll, the zest started going out of the business, and newspapers shrank their horizons,” Zoellner said.

“To this day, I think of ‘documenting the world’ as one of the most honorable professions; it’s also the mission of academia.” Tom Zoellner, professor in English.

Thankfully for Wilkinson College, Zoellner found his way to the academic world and continued his love of writing, but this time around, researching and writing non-fiction books rather than newspaper articles.

Voice of Wilkinson talked to The New York Times bestselling author (Uranium, Train and The Heartless Stone) about his latest book, Island on Fire: The Revolt that Ended Slavery in the British Empire, now available from Harvard University Press.

•••

Voice of Wilkinson: Can you give us a quick synopsis of Island on Fire?

Professor of English in Wilkinson College and author of Island on Fire: The Revolt that Ended Slavery in the British Empire, Tom Zoellner.

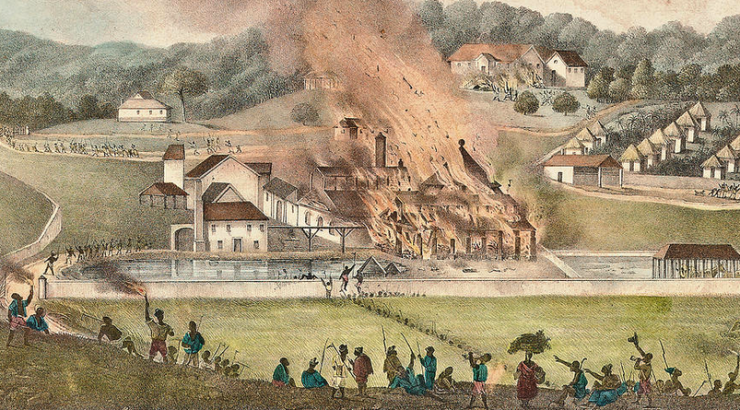

Tom Zoellner: In 1831, some of the most abused people on the globe — a group of Jamaican slaves — figured out a way to resist their captors that made a powerful impression on [the British] Parliament an ocean away. Their rebellion failed in a military sense. But within eighteen months of the first fires, slavery had been abolished as a direct result, and Britain was able to save itself the far more costly reckoning which would land in America three decades later.

VoW: What made you want to write about this history?

TZ: It started as a wide-screen global project about sugar: the nutritionally worthless product that fueled the “triangle trade” of slavery. I had done some reporting in Cuba for it, and had also learned about the 1831 rebellion in the Jamaica sugar estates which had received scant attention despite its historical import. The more I learned, the more it made sense to draw the camera lens tight on this one event that also says a great deal about sugar.

VoW: Tell us about the research that went into this book.

TZ: I visited seven archives and traveled to three continents to read the documents and  visit the places where the events transpired. Though it was upsetting, it was most meaningful to see what the British had called the “Slave Coast” of Africa — the stretches of littoral ground in present-day Ghana and Benin where much of the kidnapping took place. And though most of the Jamaican sugar estates have since disappeared into the verdure and remain unmarked, I was able to locate several of the important ones and walked their perimeters.

visit the places where the events transpired. Though it was upsetting, it was most meaningful to see what the British had called the “Slave Coast” of Africa — the stretches of littoral ground in present-day Ghana and Benin where much of the kidnapping took place. And though most of the Jamaican sugar estates have since disappeared into the verdure and remain unmarked, I was able to locate several of the important ones and walked their perimeters.

VoW: What are you hoping people that read Island on Fire will learn?

TZ: That the press coverage of violence moves the needle more than the violence itself. And that the tools of resistance — an underground network, a series of safe houses, a “case officer” school of recruitment, a philosophy of nonviolence, an oath for a greater good — are in some ways latent in nature, almost like a geometric theory or a genetic code. The methods used by the rebel leader Sam Sharpe were later duplicated, for example, by causes as diverse as Irish Republicanism, Gandhi’s “truth power,” Martin Luther King, Jr’s peaceful strikes, and the French resistance to Nazism.

VoW: Are you working on anything new right now and if so, can you give us a sneak-peak?

TZ: Yes — it came together as an accident, but I also have an essay collection coming out in October. It’s called “The National Road: Dispatches from a Changing America,” and it explores the nature of the United States from the perspective that our geography means everything, often in hidden ways.

VoW: We hear you have a newborn in the house? CONGRATS!

TZ: We welcomed our son Peter Rhodes Zoellner on May 1st. He has been an absolute joy, though sleep is now a fluid concept over here.